---

author:

- name: Evelyn Metzger

orcid: 0000-0002-4074-9003

affiliations:

- ref: bsb

- ref: eveilyeverafter

- name: Claire Williams

orcid: 0000-0001-5467-149X

affiliations:

- ref: bsb

- ref: crwilliams11

execute:

eval: false

freeze: auto

message: true

warning: false

self-contained: false

code-fold: false

code-tools: true

code-annotations: hover

engine: knitr

prefer-html: true

format: live-html

---

{{< include ./_extensions/r-wasm/live/_knitr.qmd >}}

# Pathways {#sec-pathways}

```{r}

#| label: Preamble

#| eval: true

#| echo: true

#| message: false

#| code-fold: true

#| code-summary: "R code"

source("./preamble.R")

library(ggplot2)

library(stringr)

reticulate::source_python("./preamble.py")

analysis_dir <- file.path(getwd(), "analysis_results")

input_dir <- file.path(analysis_dir, "input_files")

output_dir <- file.path(analysis_dir, "output_files")

analysis_asset_dir <- "./assets/analysis_results" # <1>

ct_dir <- file.path(output_dir, "ct")

pw_dir <- file.path(output_dir, "pathways")

if(!dir.exists(pw_dir)){

dir.create(pw_dir, recursive = TRUE)

}

results_list_file = file.path(analysis_dir, "results_list.rds")

if(!file.exists(results_list_file)){

results_list <- list()

saveRDS(results_list, results_list_file)

} else {

results_list <- readRDS(results_list_file)

}

# results_list$run_explainer <- TRUE

source("./helpers.R")

library(ComplexHeatmap)

library(circlize)

```

## Introduction

In the previous chapters, we defined "who" is in the tissue (cell

types) and where they are located (spatial domains). The next logical step is to

ask: "what are they doing?". This is a particularly exciting and open-ended question.

Since we have access to the whole transcriptome, we can measure biological activity

with unparalleled precision and down to the subcellular level, if desired.[^1]

[^1]: To keep this primer clear and tractable, we'll focus on a smaller pathway database

at the single-cell level.

Pathway analysis allows us to move beyond simple

identity markers to infer the active biological processes driving the tissue's

organization. For example, identifying a cell as a "fibroblast" tells us its

lineage, but pathway analysis tells us if that fibroblast is actively building

scar tissue (TGF-$\beta$ signaling) or recruiting immune cells (NF-$\kappa$B

signaling).

While we can measure thousands of pathways from any number of databases, in this

primer we'll keep things tractable and estimate the activity of 14 cancer-relevant

signaling pathways using the PROGENy @progeny database (see below).

Here is our approach:

1. Smoothing: We will apply nearest neighbor smoothing to borrow

information from similar cells, overcoming the sparsity of single-cell data.

2. Scoring: We will calculate an activity score for each

pathway in every single cell using the python package decoupler @decoupler.

3. Inference: We will aggregate these scores by cell type and spatial domain to

interpret signaling landscapes that define dominant biological programs and

their spatial context within the tissue.

This workflow will allow us to answer questions like:

- Is the tumor driving angiogenesis, or is the stroma?

- Which immune cells are actively inflamed versus suppressed?

- Does the "Desmoplastic Stroma" domain have a distinct signaling signature?

## Processing

Read the annData object.

```{python}

if 'adata' not in dir():

filename = os.path.join(r.analysis_dir, "anndata-7-domain_annotations.h5ad")

adata = ad.read_h5ad(filename)

adata.obsm['spatial'][:,1] *= -1 # <1>

```

1. flipping the y-axis so that the tissue is in the same orientation as the

rest of the analysis.

We'll use the PROGENy (Pathway RespOnsive GENes) @progeny database available within decoupler @decoupler to estimate

the single cell enrichment

scores of each of the 14 cancer-relevant pathways and their significant values.

PROGENy is a resource that estimates pathway activity by analyzing the downstream

genes known to change in response to perturbation experiments across a wide variety

of human cancer cell lines. I find that it is useful in a wide range of cancer samples

but it might not be ideal for, say, transplant or viral infection samples.

The code below adapts [decoupler's tutorial](https://decoupler.readthedocs.io/en/latest/notebooks/scell/rna_pstime.html#progeny-pathway-genes){target="_blank"} which uses the [univarte linear model method (ulm) function](https://decoupler.readthedocs.io/en/latest/api/generated/decoupler.mt.ulm.html){target="_blank"}.

PROGENy can provide a high-level overview of the tissue's

molecular functions distilled down to a handful of pathways -- which is relatively

quick. For non-cancer systems, or if greater resolution is desired, other databases

can be used with the `ulm` approach. If you are interested in exploring other

databases within decoupler, run `decoupler.op.show_resources()`.

Here's a description of those pathways from decoupler's website.

```

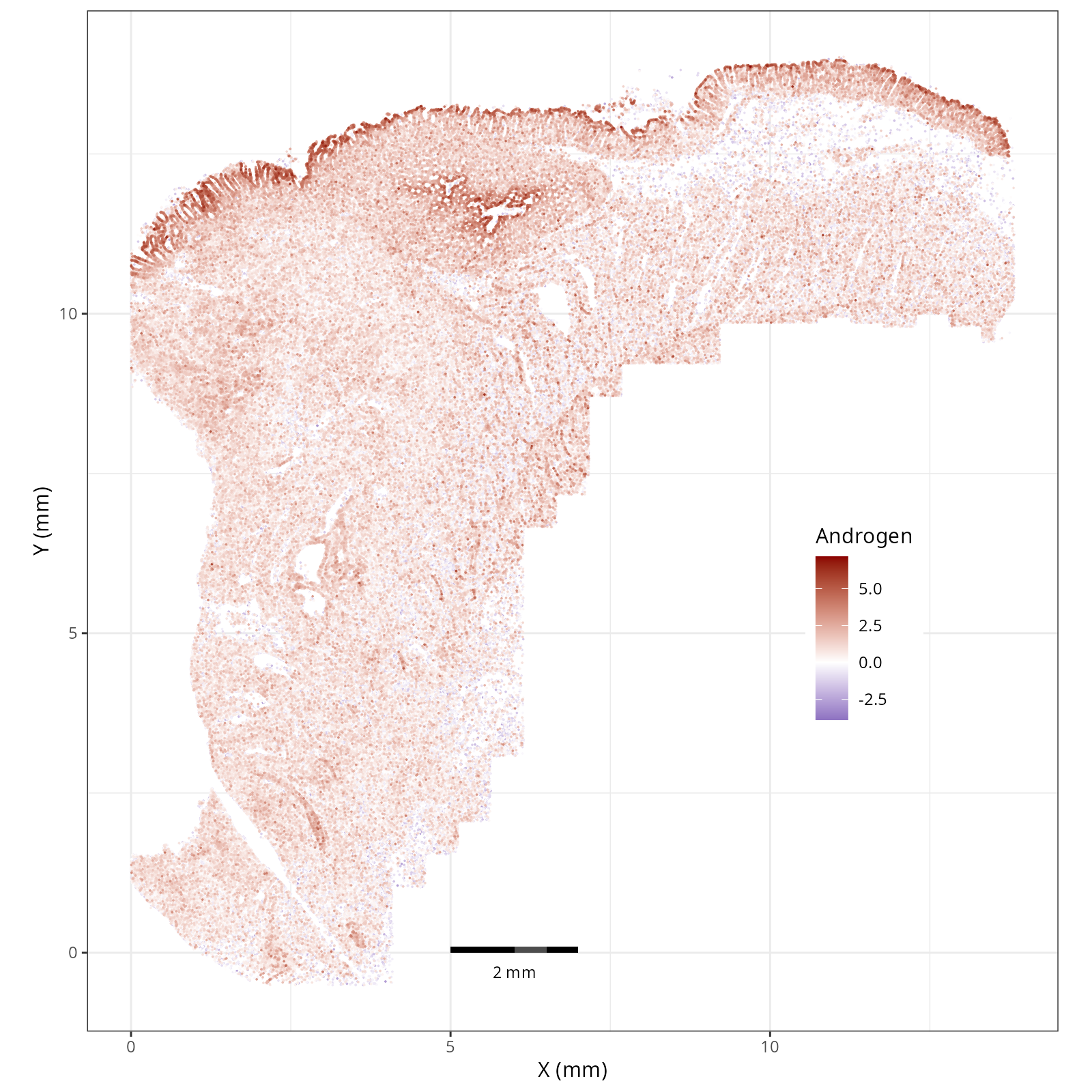

- Androgen: involved in the growth and development of the male reproductive organs.

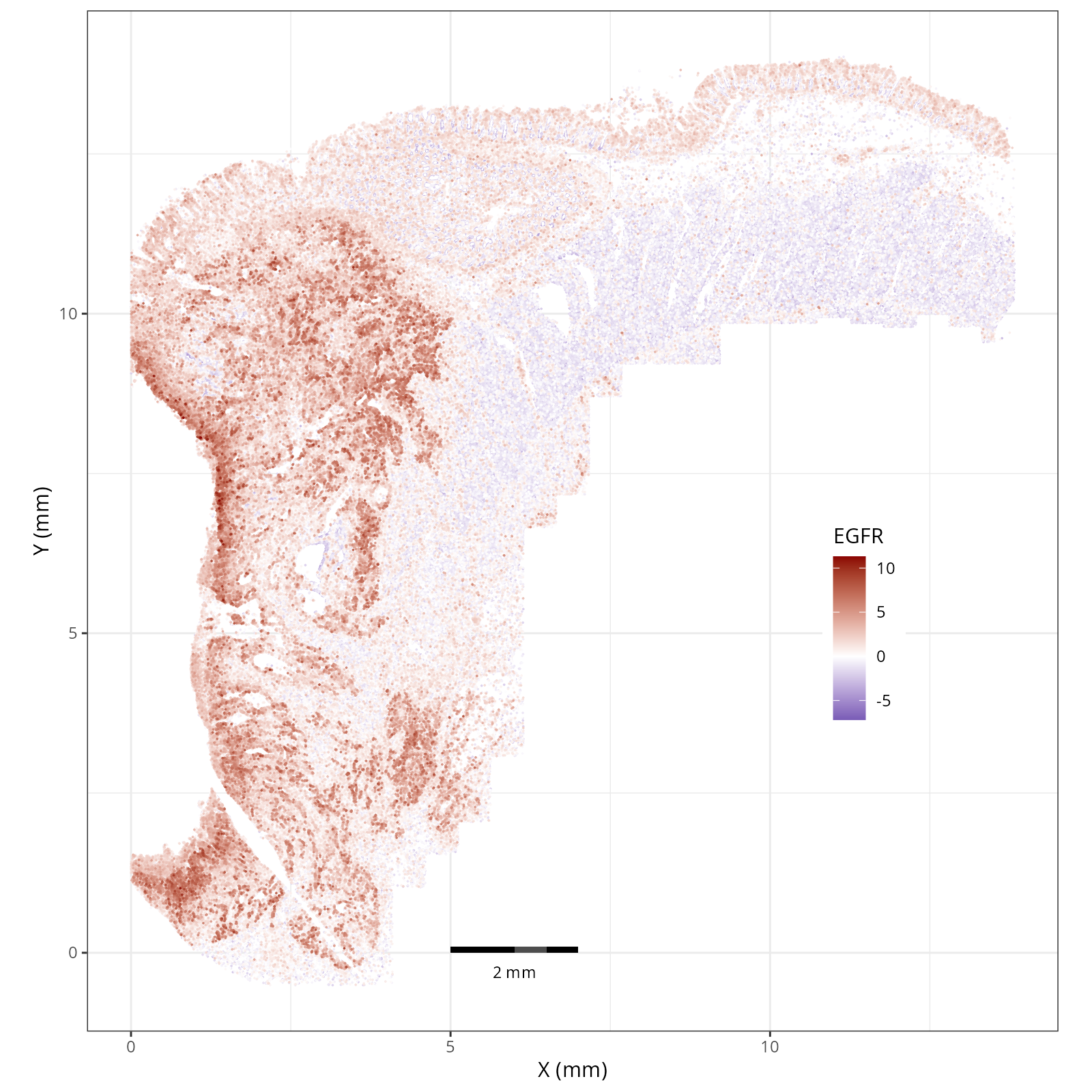

- EGFR: regulates growth, survival, migration, apoptosis, proliferation, and differentiation in mammalian cells

- Estrogen: promotes the growth and development of the female reproductive organs.

- Hypoxia: promotes angiogenesis and metabolic reprogramming when O2 levels are low.

- JAK-STAT: involved in immunity, cell division, cell death, and tumor formation.

- MAPK: integrates external signals and promotes cell growth and proliferation.

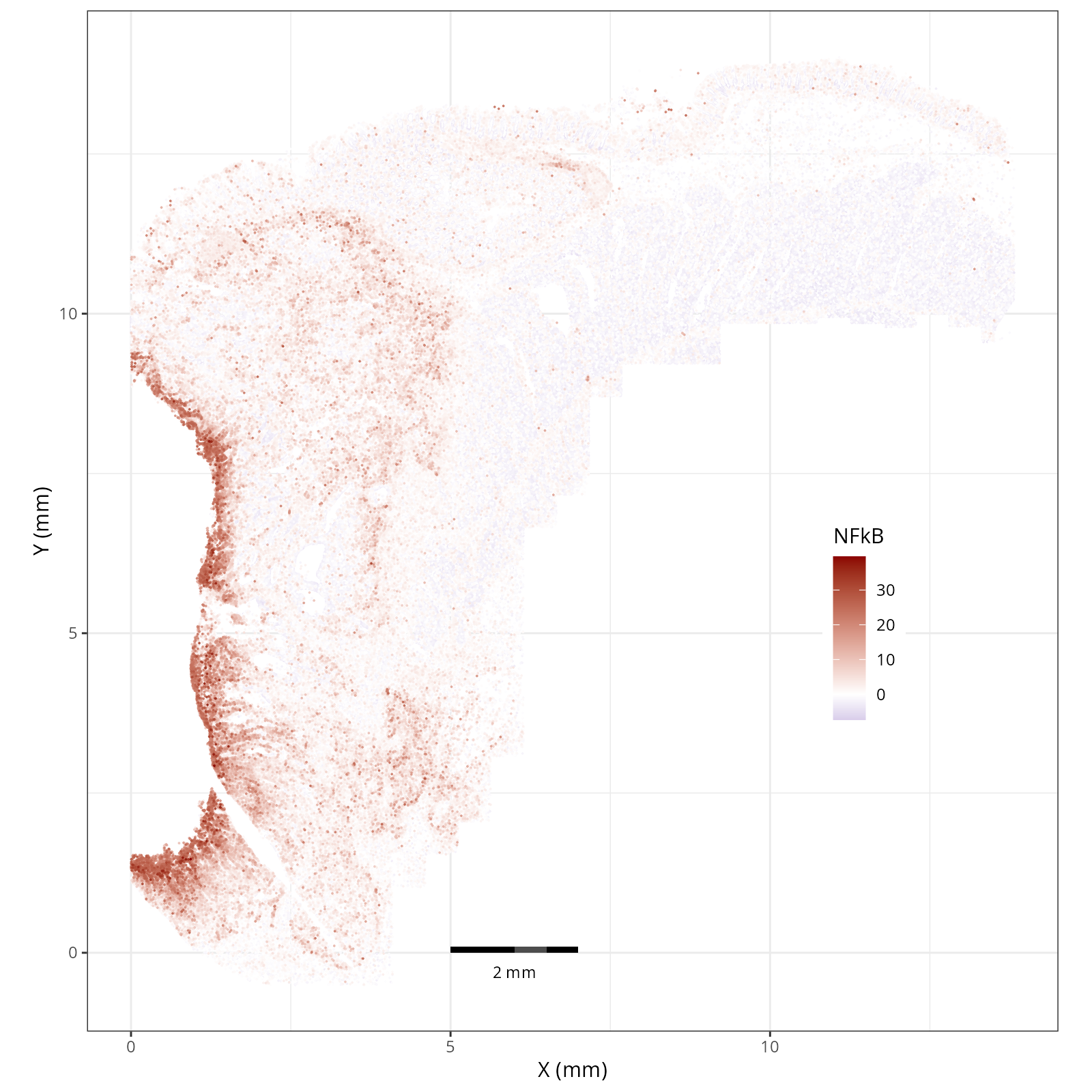

- NFkB: regulates immune response, cytokine production and cell survival.

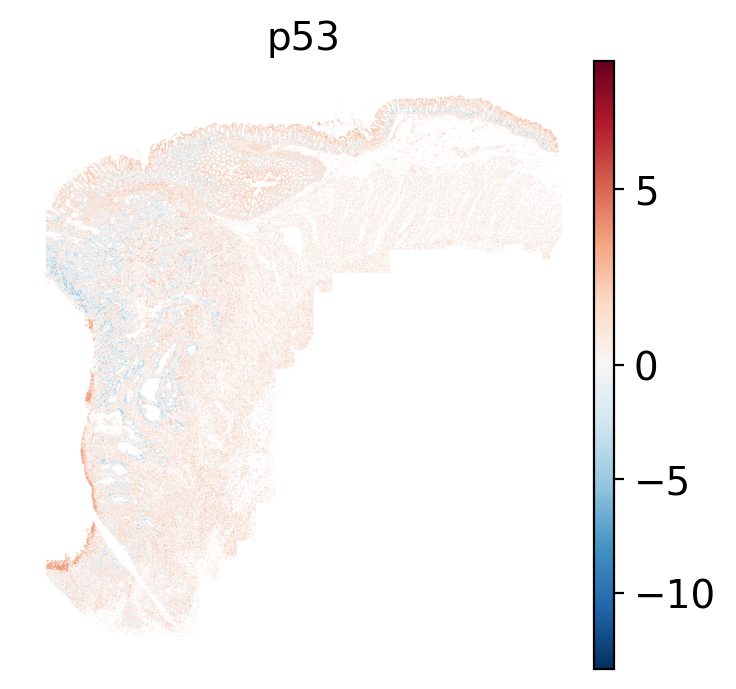

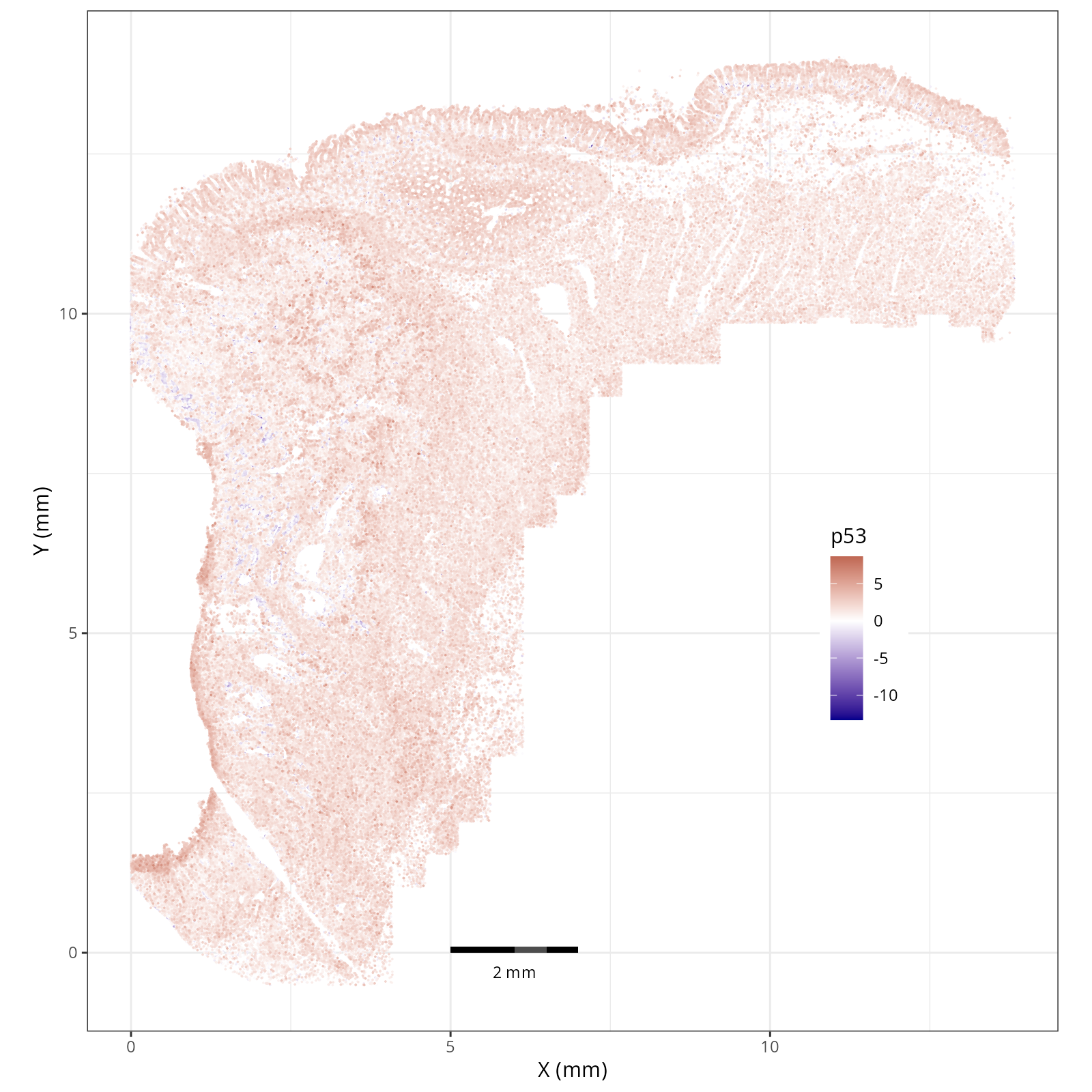

- p53: regulates cell cycle, apoptosis, DNA repair and tumor suppression.

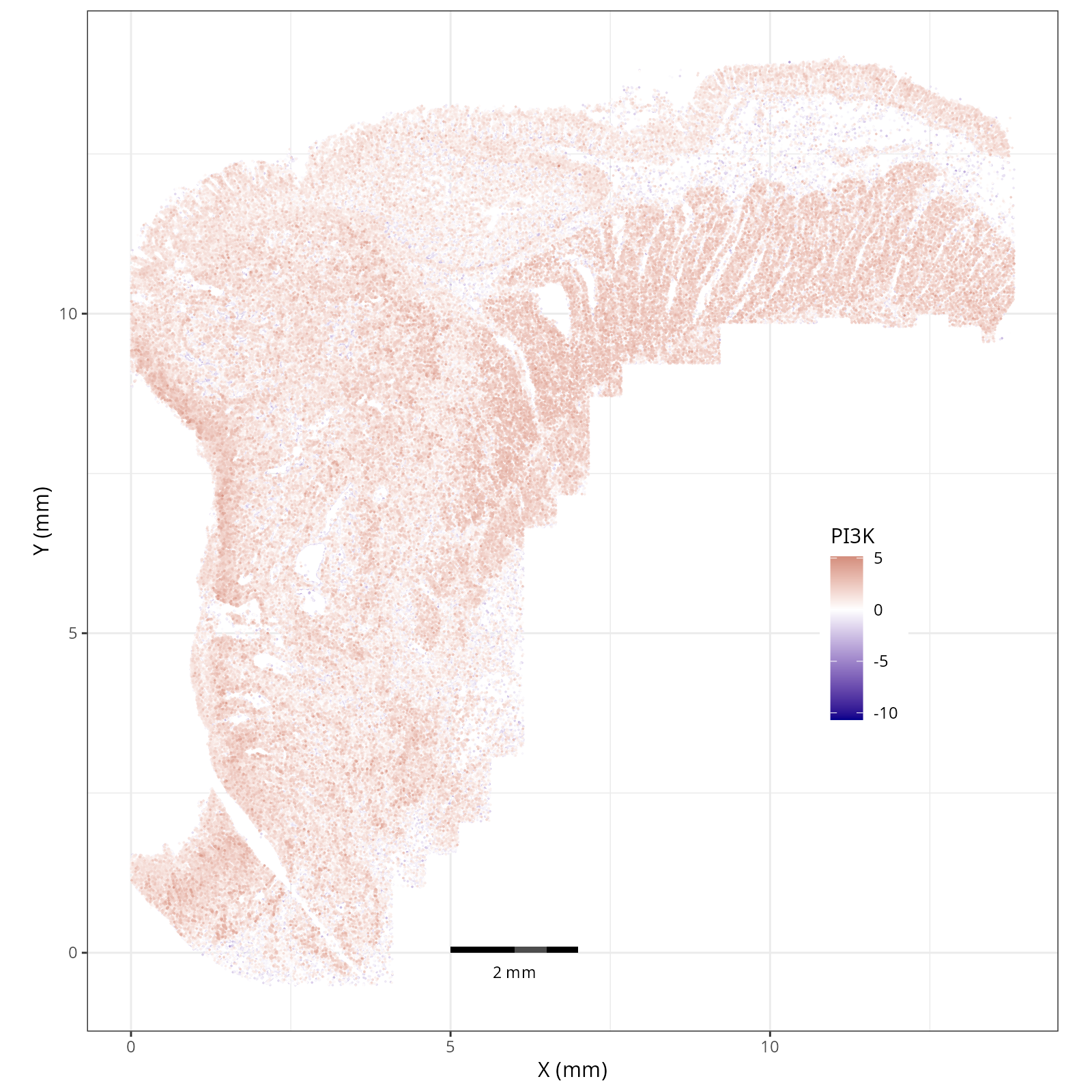

- PI3K: promotes growth and proliferation.

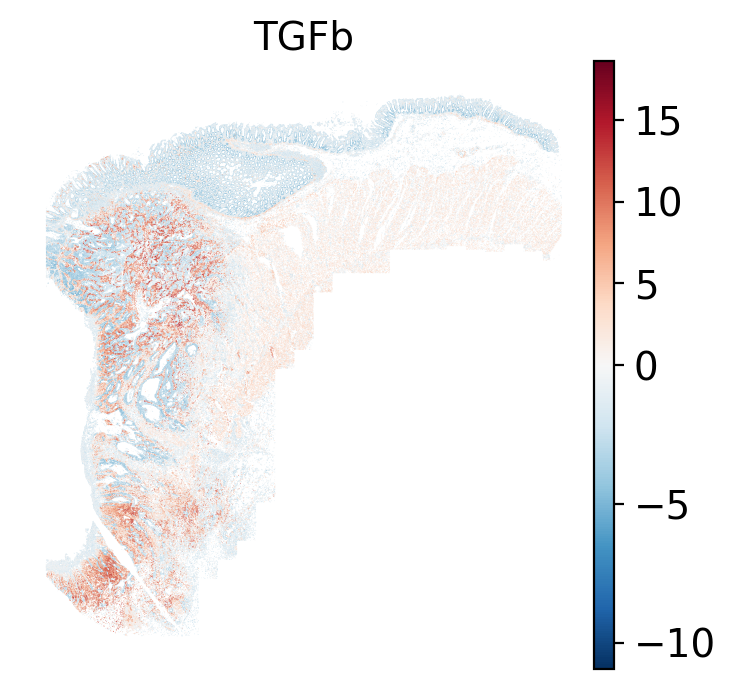

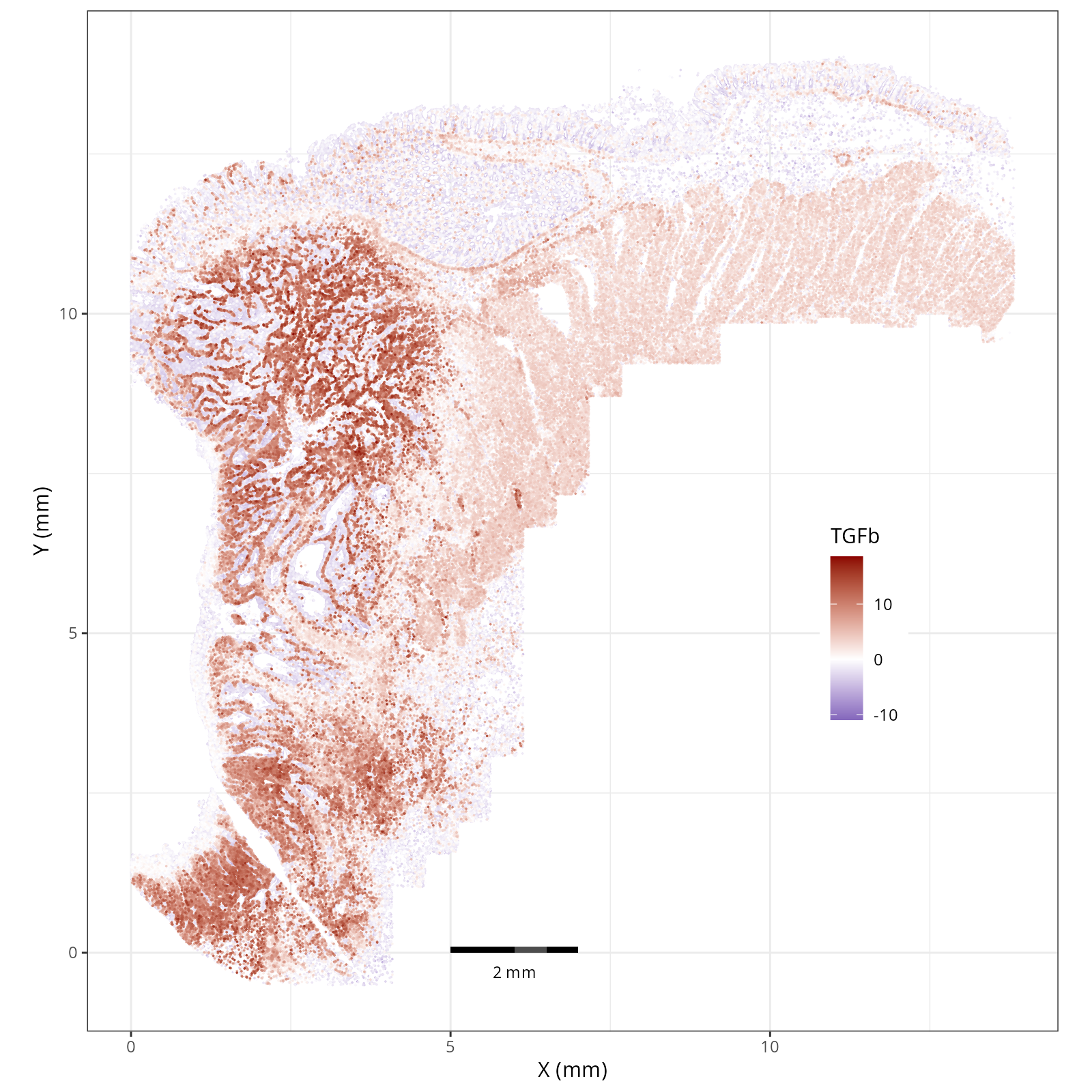

- TGFb: involved in development, homeostasis, and repair of most tissues.

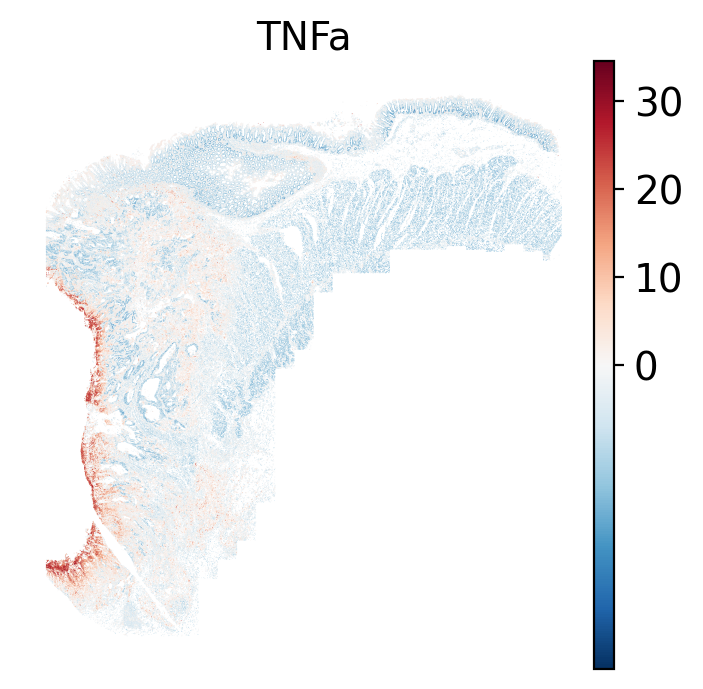

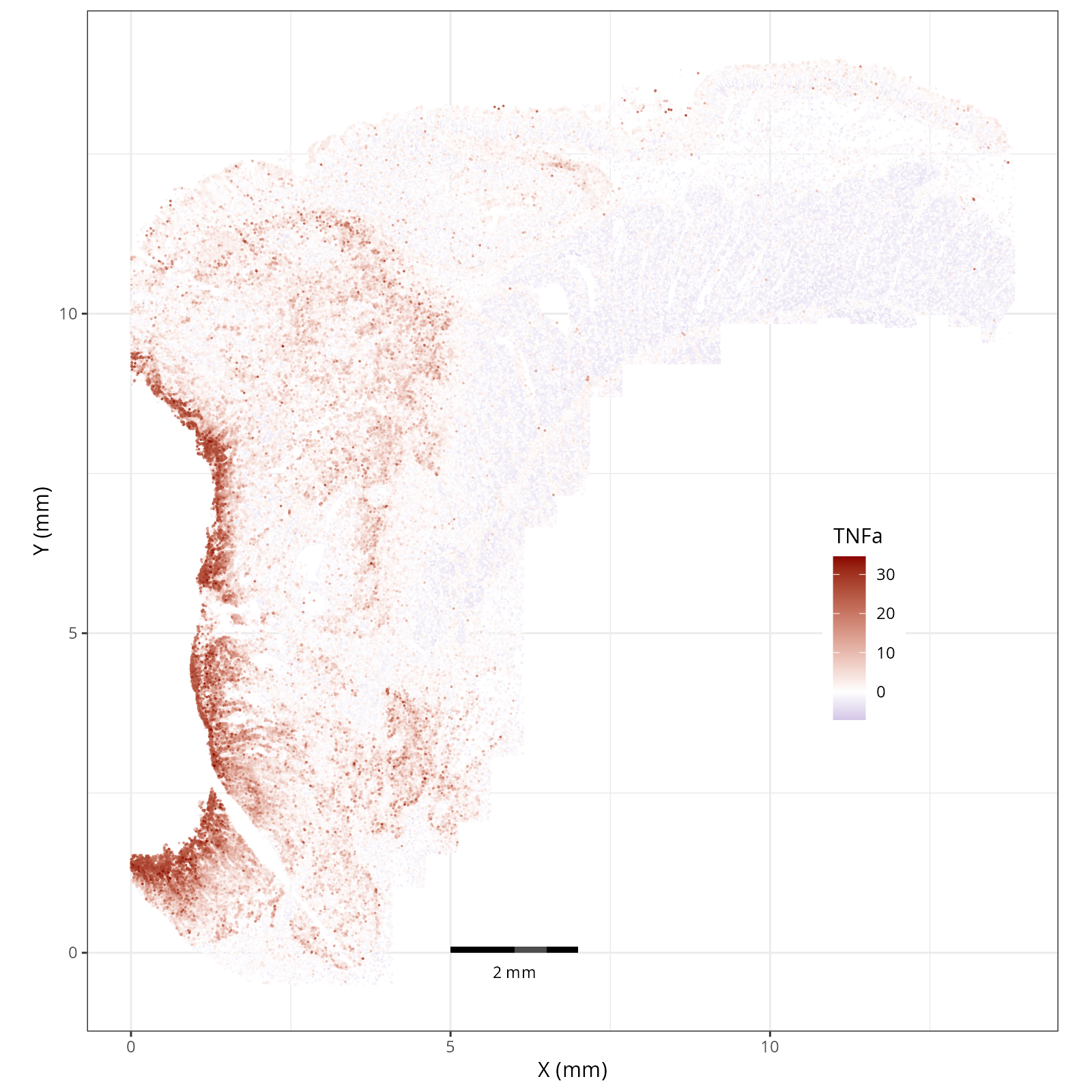

- TNFa: mediates haematopoiesis, immune surveillance, tumour regression and protection from infection.

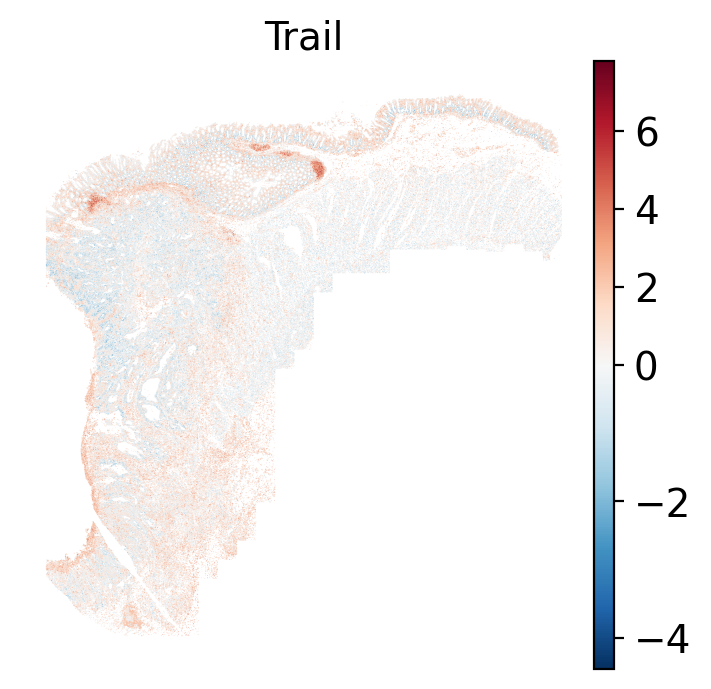

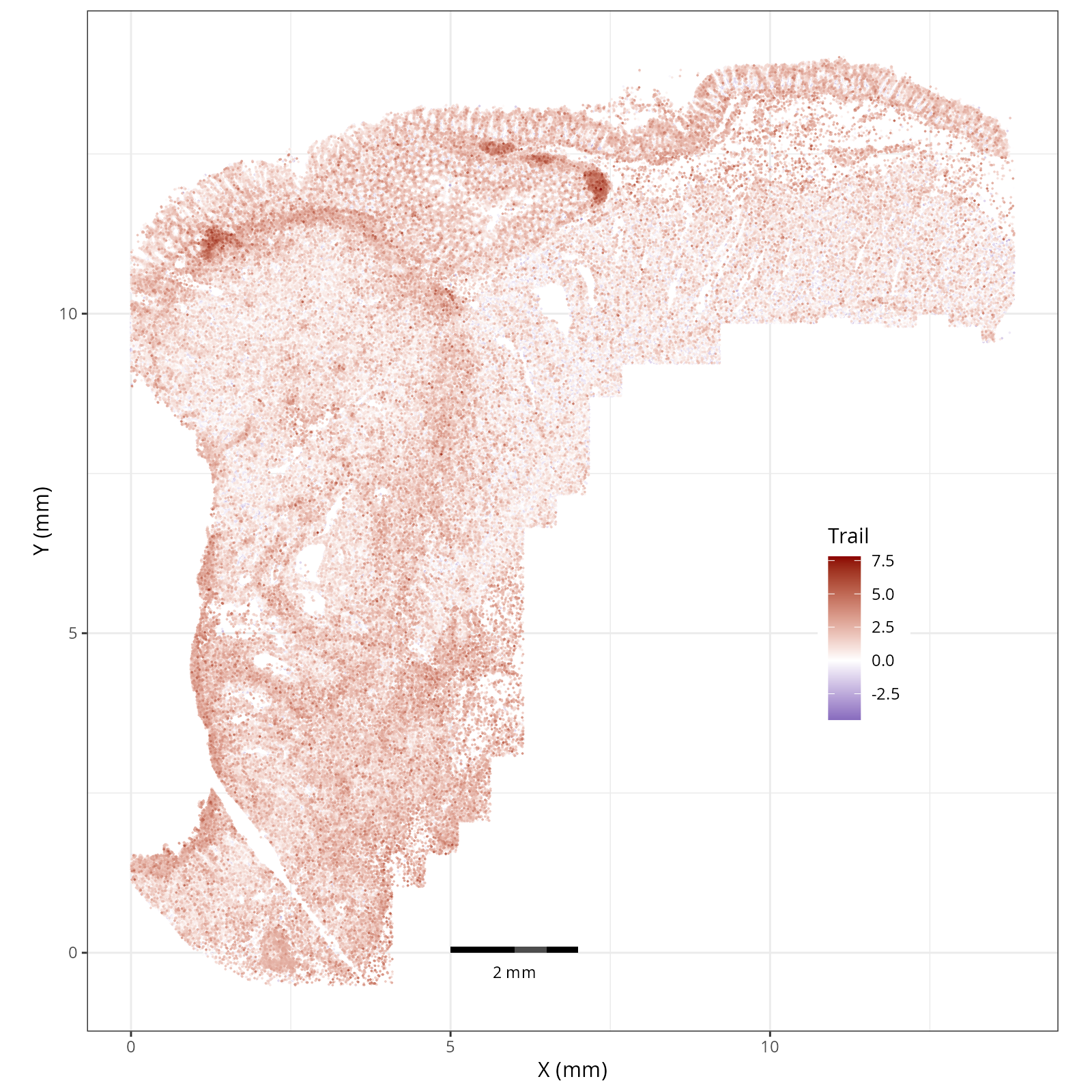

- Trail: induces apoptosis.

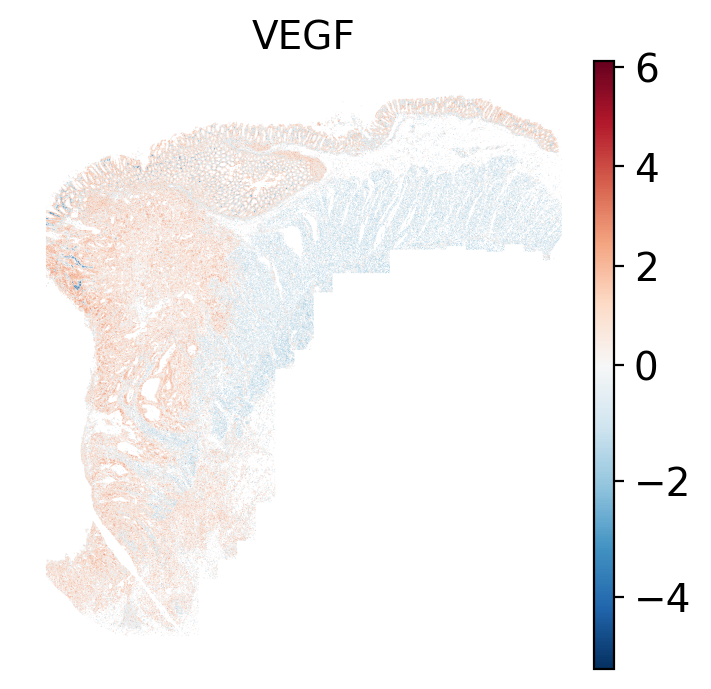

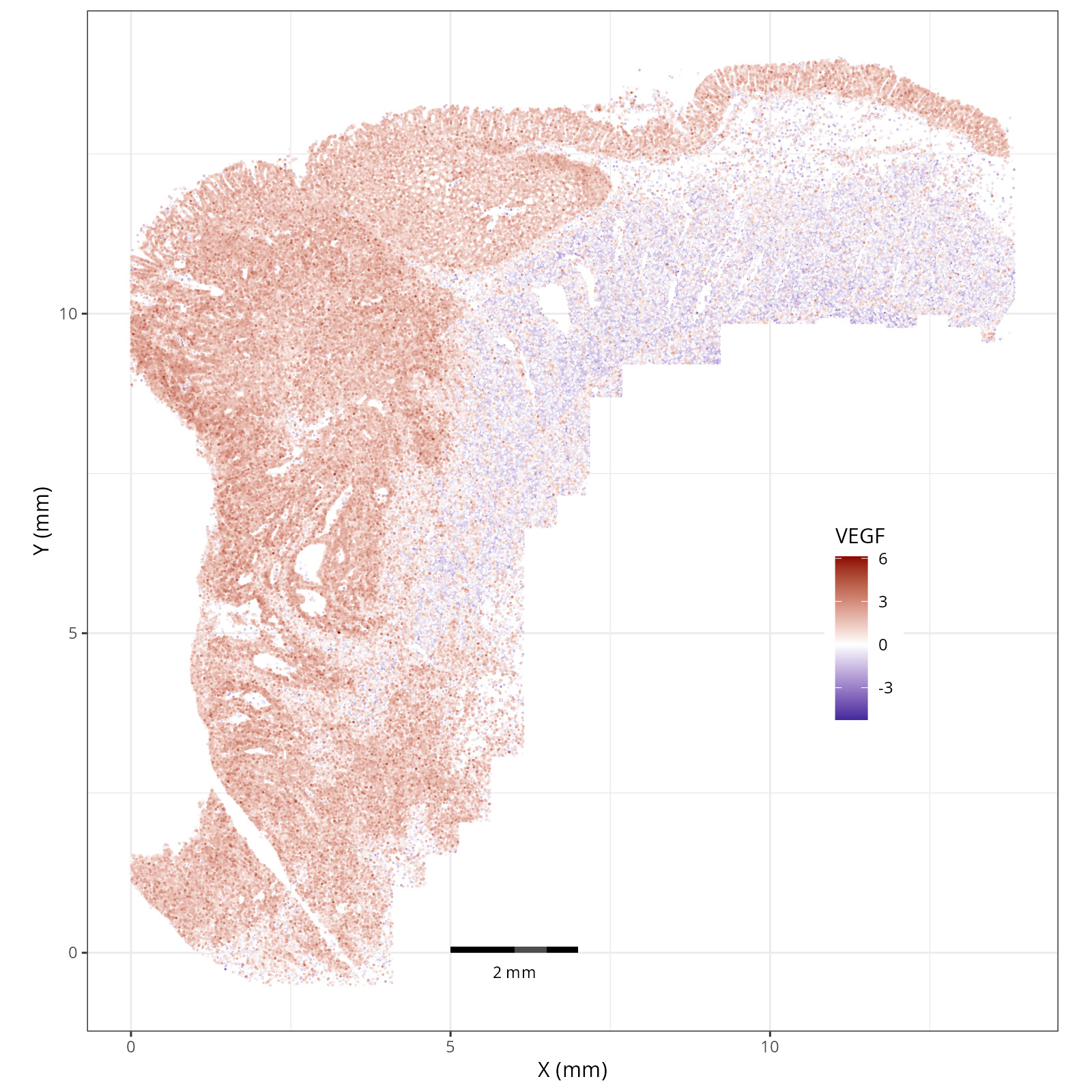

- VEGF: mediates angiogenesis, vascular permeability, and cell migration.

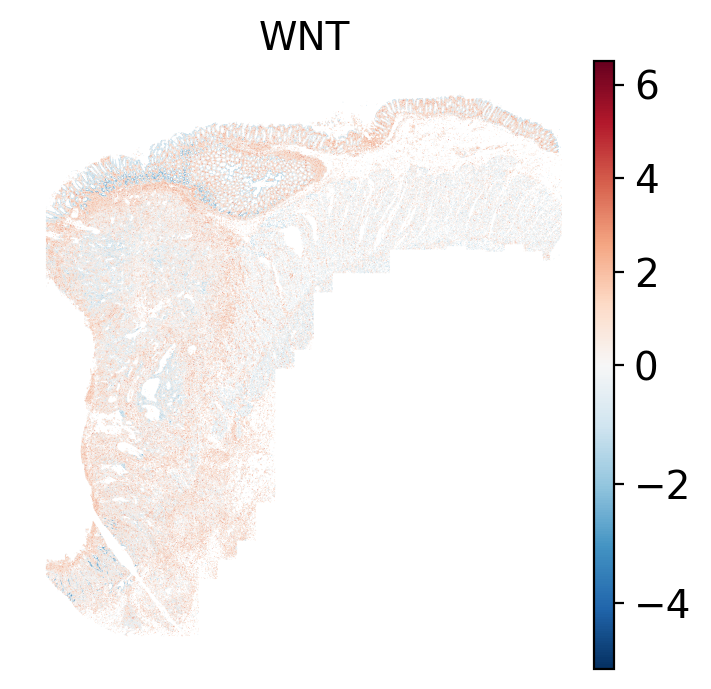

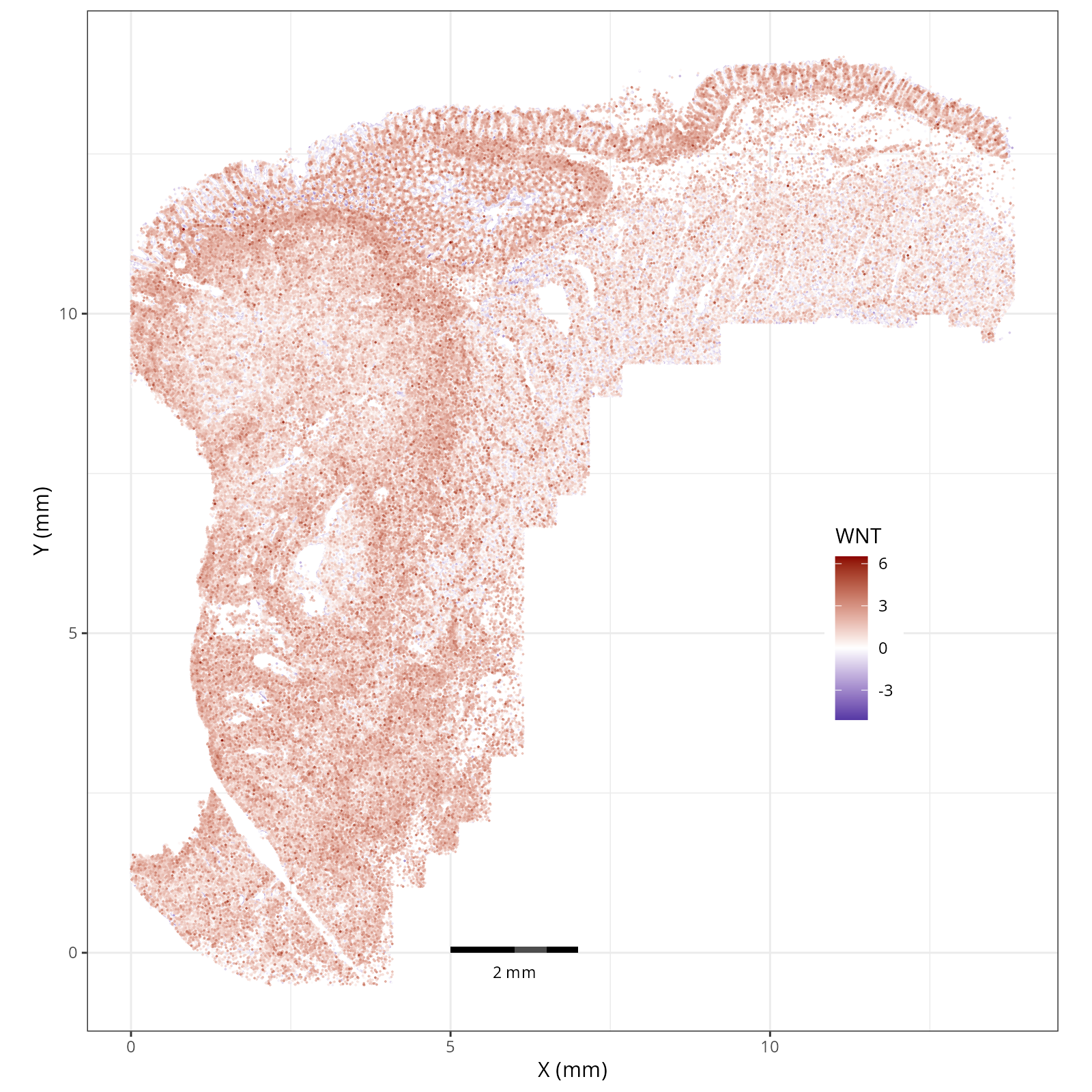

- WNT: regulates organ morphogenesis during development and tissue repair.

```

Let's load the PROGENy dataset.

```{python}

#| label: load-progeny

#| eval: false

#| code-summary: "Python Code"

#| message: false

#| warning: false

#| code-fold: true

import decoupler as dc

progeny = dc.op.progeny(organism='human', top=500, license="commercial")

progeny_genes = progeny['target'].unique()

```

```{r}

results_list['n_progeny_genes'] = length(py$progeny_genes)

saveRDS(results_list, results_list_file)

```

For the analysis below we'll need normalized data. As we saw in @sec-preprocessing,

we bypassed the creation of the dense Pearson Residuals normalization matrix

and used the PCs instead for nearest neighbors calculations, Leiden, _etc_.

The main reason for this was computational tractability (>400,000 cells by _ca_. 19,000 targets).

That issue is still present here. There are only `r as.numeric(results_list['n_progeny_genes'])` genes

in the pathway database that we chose and so we do not necessarily need to normalized

the entire matrix. Scanpy has a method for Pearson Residuals normalization

(`sc.experimental.pp.normalize_pearson_residuals`) but there's a catch: ideally we

would _not_ run Pearson Normalization on a subset of features. Instead, we would like

the non-truncated transcript totals to factor into the normalization procedure.

We can achieve this by creating a custom code.

```{python}

#| label: normalize

#| eval: false

#| code-summary: "Python Code"

#| message: false

#| warning: false

#| code-fold: show

# 1. Get valid genes

# these are the ones that are in BOTH the progeny dataset and in the anndata, adata

valid_genes = [g for g in progeny_genes if g in adata.var_names]

# 2. Get GLOBAL Stats (before subsetting)

counts_layer = adata.layers['counts'] if 'counts' in adata.layers else adata.X

global_cell_sums = np.array(counts_layer.sum(axis=1)).flatten() # or just from nCount_RNA

total_count = global_cell_sums.sum() # i.e., sum(obs$nCount_RNA)

# 3. Get GENE Stats (Just for the subset is all that's necessary)

gene_indices = [adata.var_names.get_loc(g) for g in valid_genes]

subset_gene_sums = np.array(counts_layer.sum(axis=0)).flatten()[gene_indices]

# 4. Create the Subset

adata_sub = adata[:, valid_genes].copy()

# Ensure we are using raw counts for the calculation

if 'counts' in adata_sub.layers:

adata_sub.X = adata_sub.layers['counts'].copy()

# 5. Expected counts based on global depth (from the full dataset)

mu = np.outer(global_cell_sums, subset_gene_sums) / total_count

# Pearson Residuals: (Observed - Expected) / StdDev

theta = 100

observed = adata_sub.X.toarray()

residuals = (observed - mu) / np.sqrt(mu + mu**2 / theta)

# Clip outliers (similar to what scanpy does)

clip_val = np.sqrt(adata_sub.shape[0])

residuals = np.clip(residuals, -clip_val, clip_val)

# 6. Save results

adata_sub.X = residuals

del adata

adata = adata_sub

# Clean up

import gc

del adata_sub, mu, observed, residuals, global_cell_sums, subset_gene_sums

gc.collect()

```

At this point the anndata object has many components that are not needed.

Let's reduce the size of this object to reduce the memory footprint.

```{python}

#| label: trim

#| eval: false

#| code-summary: "Python Code"

#| message: false

#| warning: false

#| code-fold: show

# Clean up obsm

obsm_delete = ['X_pca_TC', 'counts_neg', 'counts_sys', 'umap_TC']

for x in obsm_delete:

if x in adata.obsm:

del adata.obsm[x]

# Clean up obsp

obsp_delete = ['neighbors_TC_connectivities', 'neighbors_TC_distances']

for x in obsp_delete:

if x in adata.obsp:

del adata.obsp[x]

gc.collect()

adata.layers['pr_norm'] = adata.X.astype('float32').copy() # <1>

```

1. Convert from float 64 bit to float 32 bit Optional step for systems with less RAM.

## Smoothing Expression

One attribute of all spatial single cell datasets relative to non-spatial method

is sparsity. Even for technologies with high-sensitivity detection, individual cells

may lack the detection of every transcript required to precisely score pathways.

To overcome this, tools like decoupler and liana @Dimitrov2022 @Dimitrov2024 utilize _smoothing_ -- a

process of borrowing information from neighboring cells to impute missing values

and stabilize pathway scores. However, the term "neighbor" here can be ambiguous.

Many of the existing tutorials for these tools were developed with spot-based

technologies (like Visium) in mind where _spatial smoothing_ is used because spots

are already multi-cellular mixtures. For single-cell resolution data like CosMx

SMI, the choice of using spatial smoothing depends on the types of biological

questions you have @tbl-smoothing-choices. For pathway analysis, we recommend smoothing

based on nearest expression neighbors (NN). Check back later when we release a

chapter on ligand-receptor analysis for an example of spatial smoothing.

| Feature | Nearest Expression Neighbors (NN) | Spatial Neighbors (SN) |

| :--- | :--- | :--- |

| **Definition** | Averages signal from cells with similar gene expression profiles (_e.g._, neighbors in PCA space). | Averages signal from cells physically touching or near the target cell (XY space). |

| **Primary Benefit** | **Preserves Cell Identity.** A T cell is smoothed with other T cells, maintaining lineage-specific signals. | **Visualizes Zones.** Highlights continuous tissue gradients and regional (_i.e._, multiple domain) behaviors. **Analyzing Larger Spatial Patterns** When examining zonal, regional (_e.g._, hypoxia), or other larger effects, cells are responding by an interaction of their lineage and their spatial position. Spatial smoothing in this scenario can aid in quantifying the metabolic spatial neighborhood by denoising cells with sparse data. **Ligand Receptor Analysis.** While we might not want to spatially smooth a CD4 T cell with, say, a Tumor cell, for certain analyses, this computational approach can be effective in analyzing [ligand-receptor relationships](https://liana-py.readthedocs.io/en/latest/notebooks/bivariate.html#bivariate-ligand-receptor-relationships). Essentially, if we borrow the receptor expression of nearby cells, we can then test if that receptor is correlated with the focal cells' corresponding ligand receptor expression. |

| **Drawback** | May erode any cell type by specific local/regional interaction effect. | **Signal Bleeding** Can artificially blend high-expression markers (e.g., *PTPRC*) into neighboring negative cells (e.g., Tumor). **Tuning** The degree (_e.g._, radius, Gaussian kernel) that is used for spatial smoothing is a tuning parameter that, ideally, should align the observational scale with the functional scale. |

| **Best Use Case** | Lineage-specific pathways (e.g., TCR signaling, Cell Cycle, B cell activation). | Environmental gradients that occur at regional levels not captured by expression-based domain assignments (e.g., Hypoxia, Nutrient Deprivation, pH levels). |

| **Example** | See @sec-path-enrichment below | See upcoming ligand-receptor chapter (expected early 2026) |

: Two types of smoothing and when to use them. {#tbl-smoothing-choices}

Let's apply nearest neighbor smoothing.

Recall in @sec-preprocessing we created a neighbor graph based on pearson residuals PC

values derived using the scPearsonPCA package. This produced the `neighbors_pr_connectivities`

connectivity matrix in `obsp`. We'll use this to smooth our cells' expression.

```{python}

#| eval: false

#| code-summary: "Python Code"

#| message: false

#| warning: false

#| code-fold: show

adata.layers['nn_smooth'] = adata.obsp['neighbors_pr_connectivities'] @ adata.layers['pr_norm']

```

## Pathway Enrichment {#sec-path-enrichment}

Run the univariate linear model from `decoupler` using

the PROGENy database with this smoothed expression matrix to generate pathway

scores. Save the results.

```{python}

#| label: nn-run-ulm

#| eval: false

#| code-summary: "Python Code"

#| message: false

#| warning: false

#| code-fold: show

dc.mt.ulm(

data=adata,

net=progeny,

verbose=True,

layer=f'nn_smooth',

bsize=80000

)

filename = os.path.join(r.analysis_dir, "anndata-8-pathways-nn.h5ad")

adata.write_h5ad(

filename,

compression=hdf5plugin.FILTERS["zstd"],

compression_opts=hdf5plugin.Zstd(clevel=5).filter_options

)

```

## Visualizing Pathway Enrichment

We'll visualize the pathways "locally" on the tissue as well as "globally" by creating

heatmaps per cell type and domain.

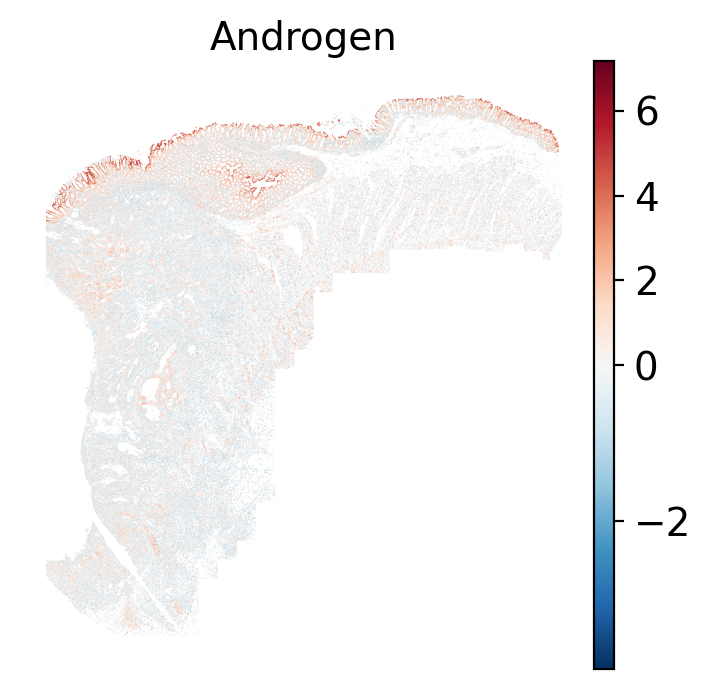

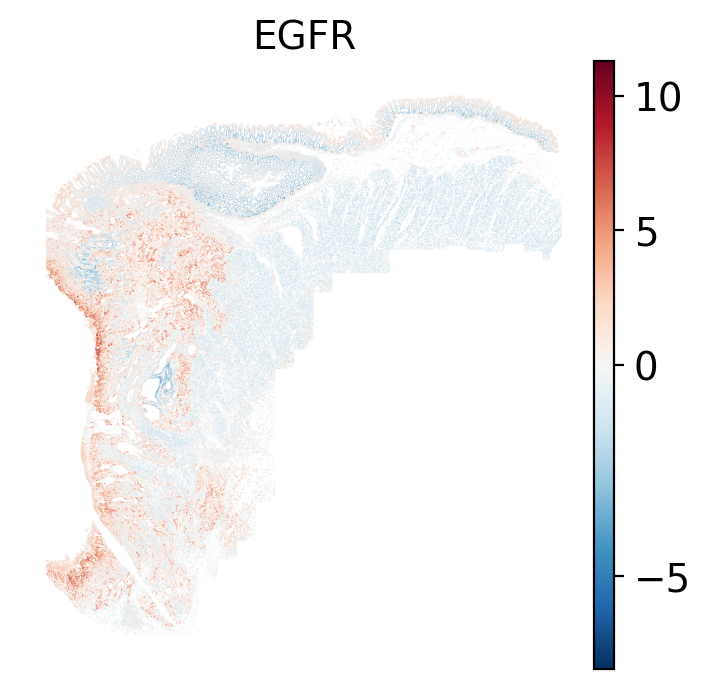

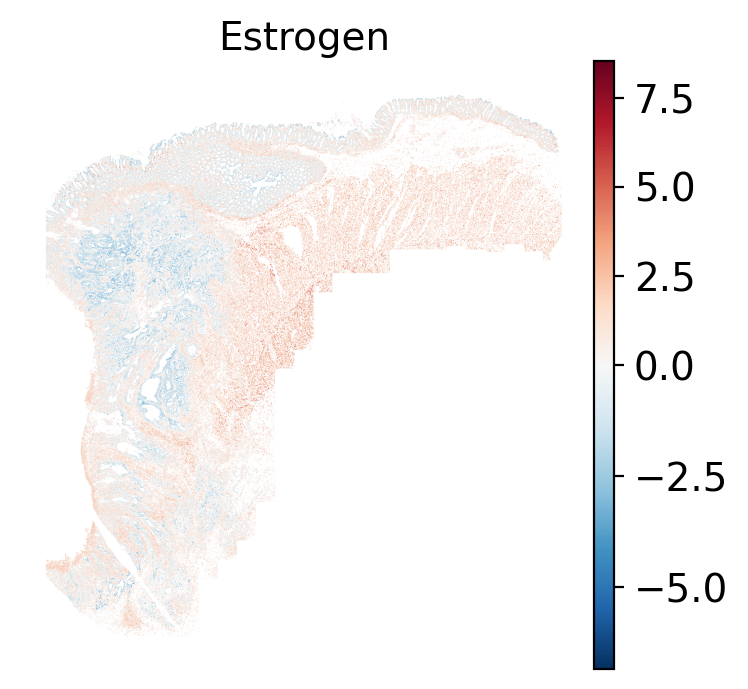

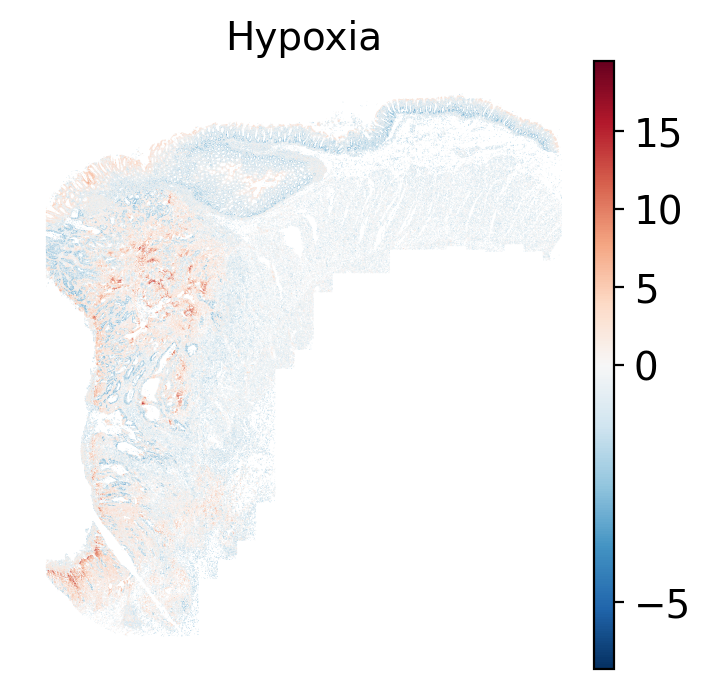

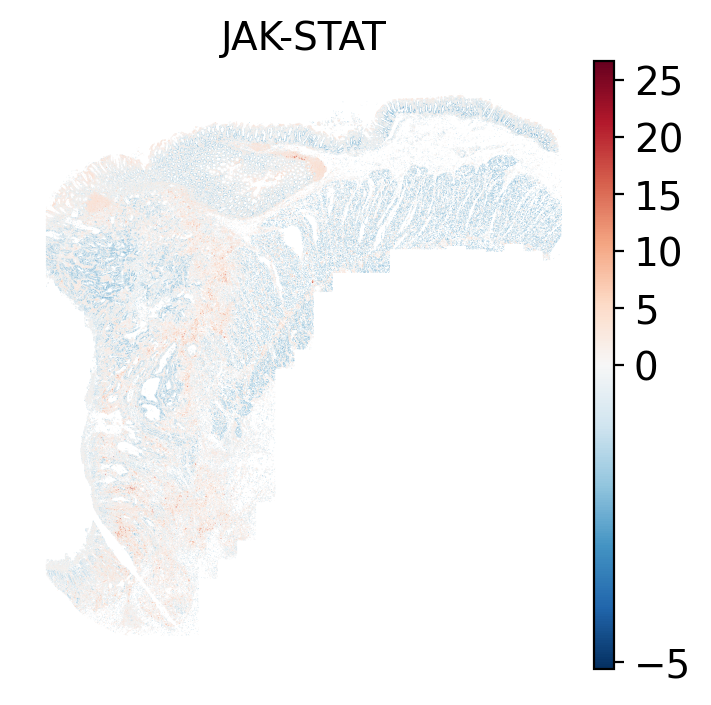

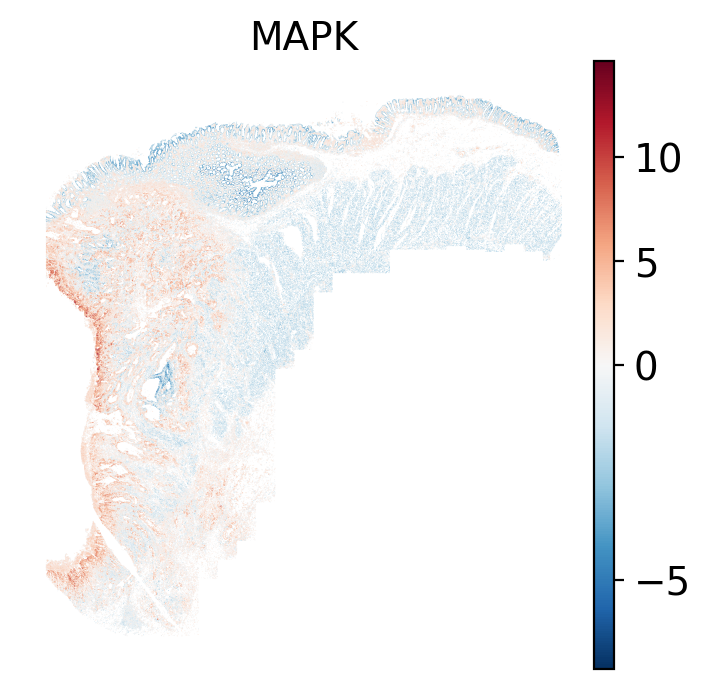

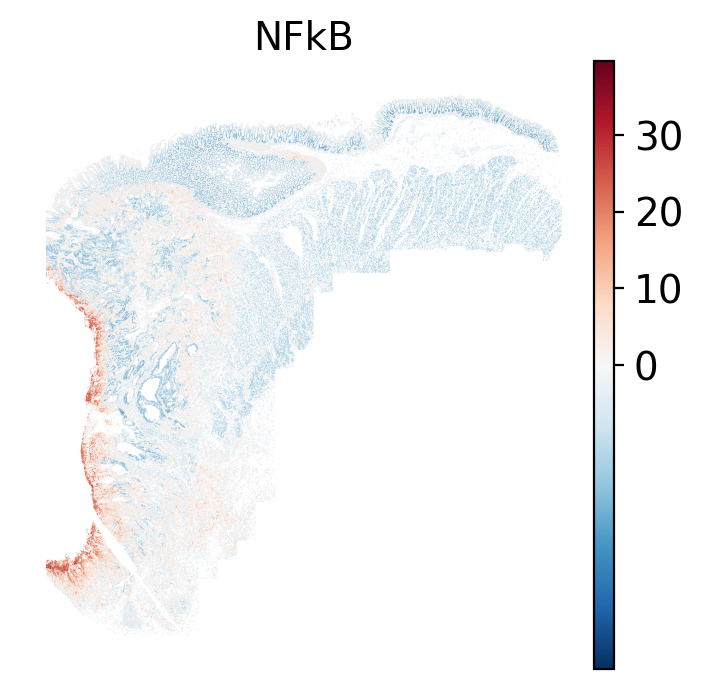

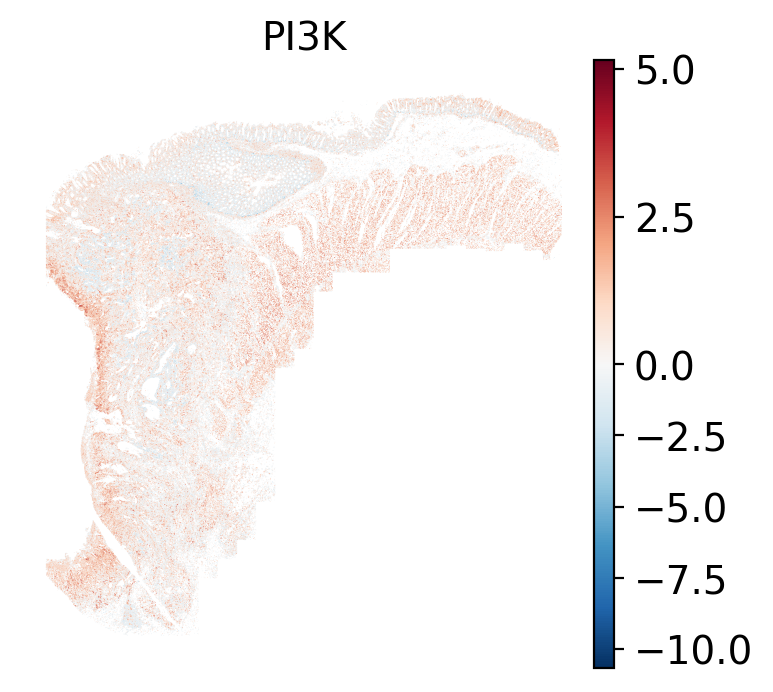

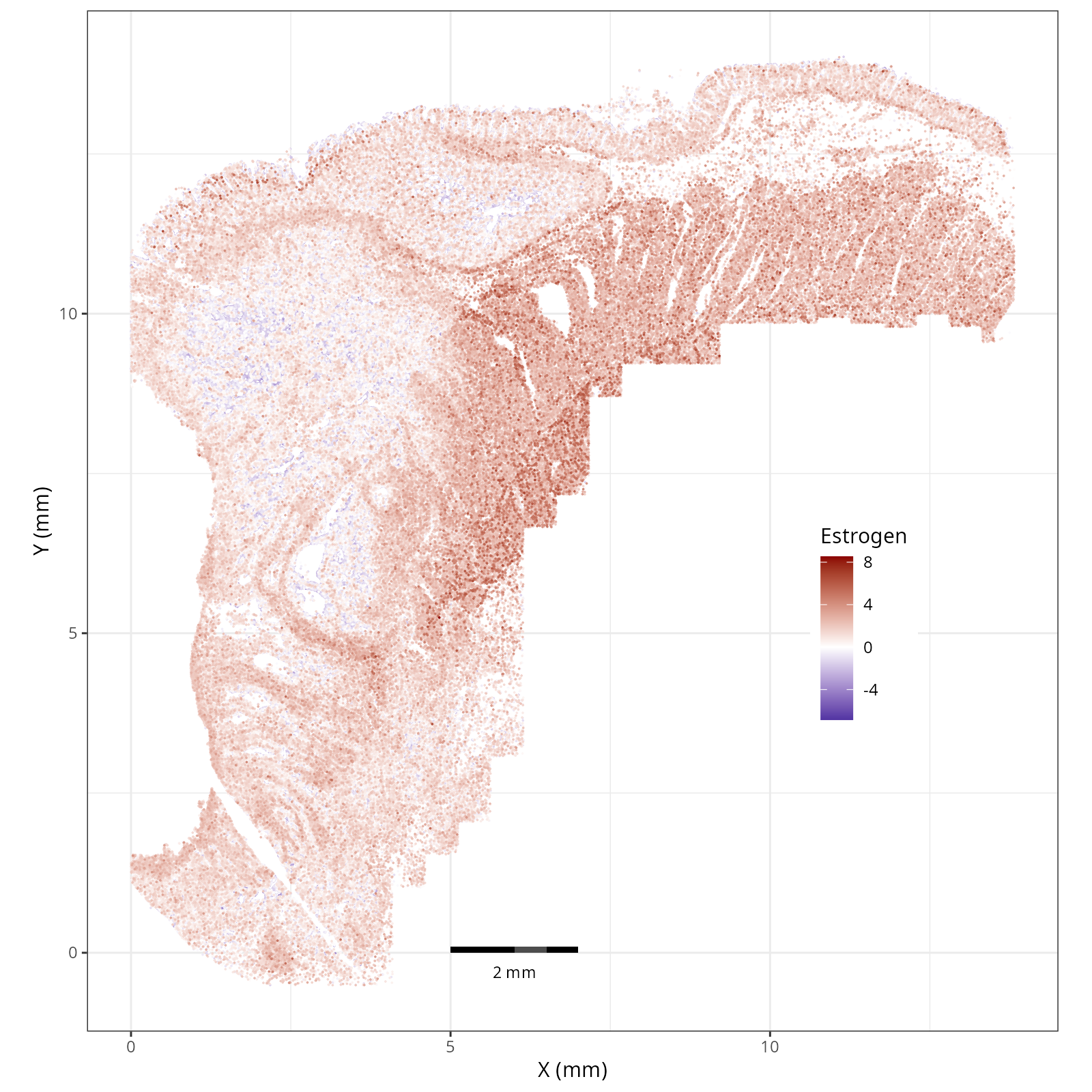

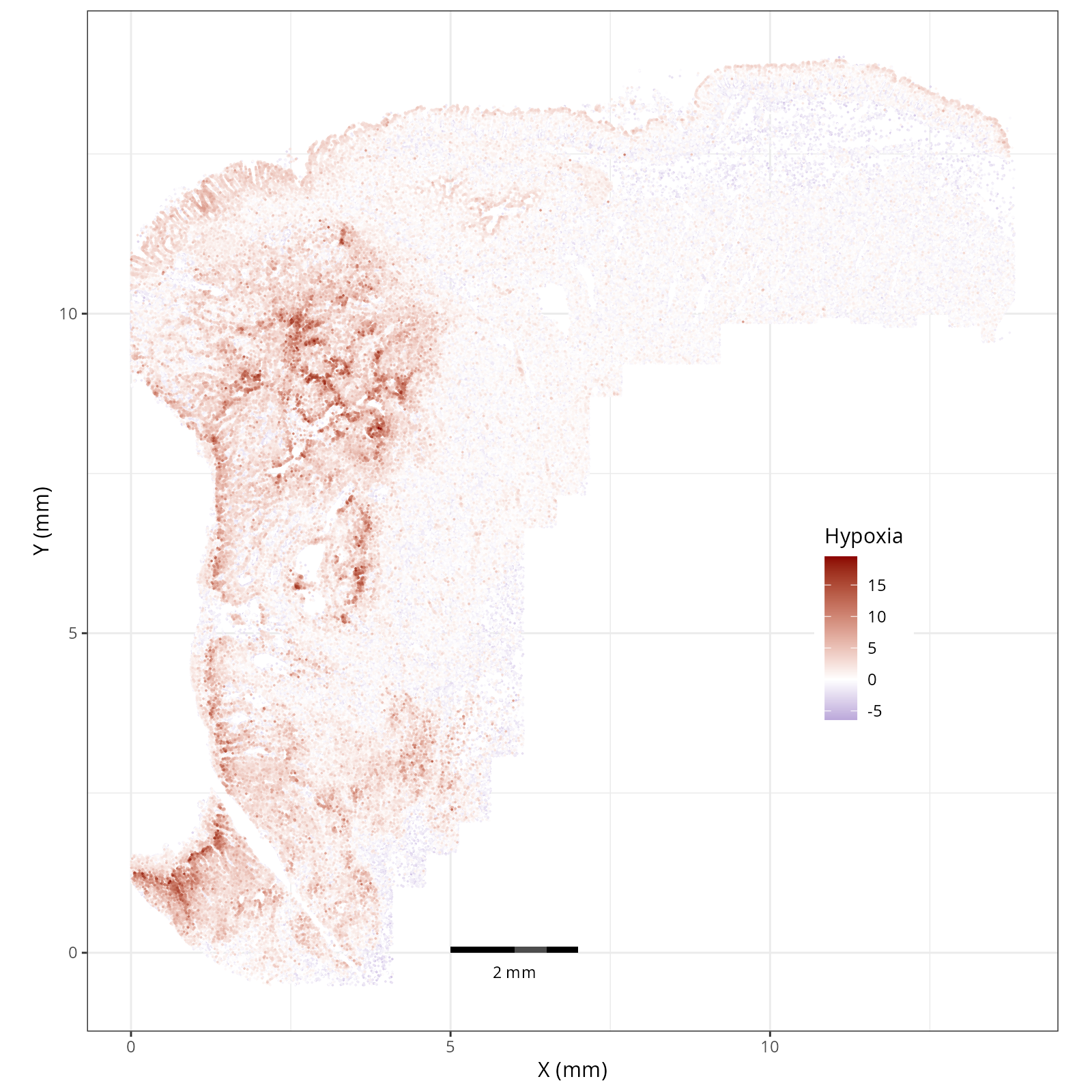

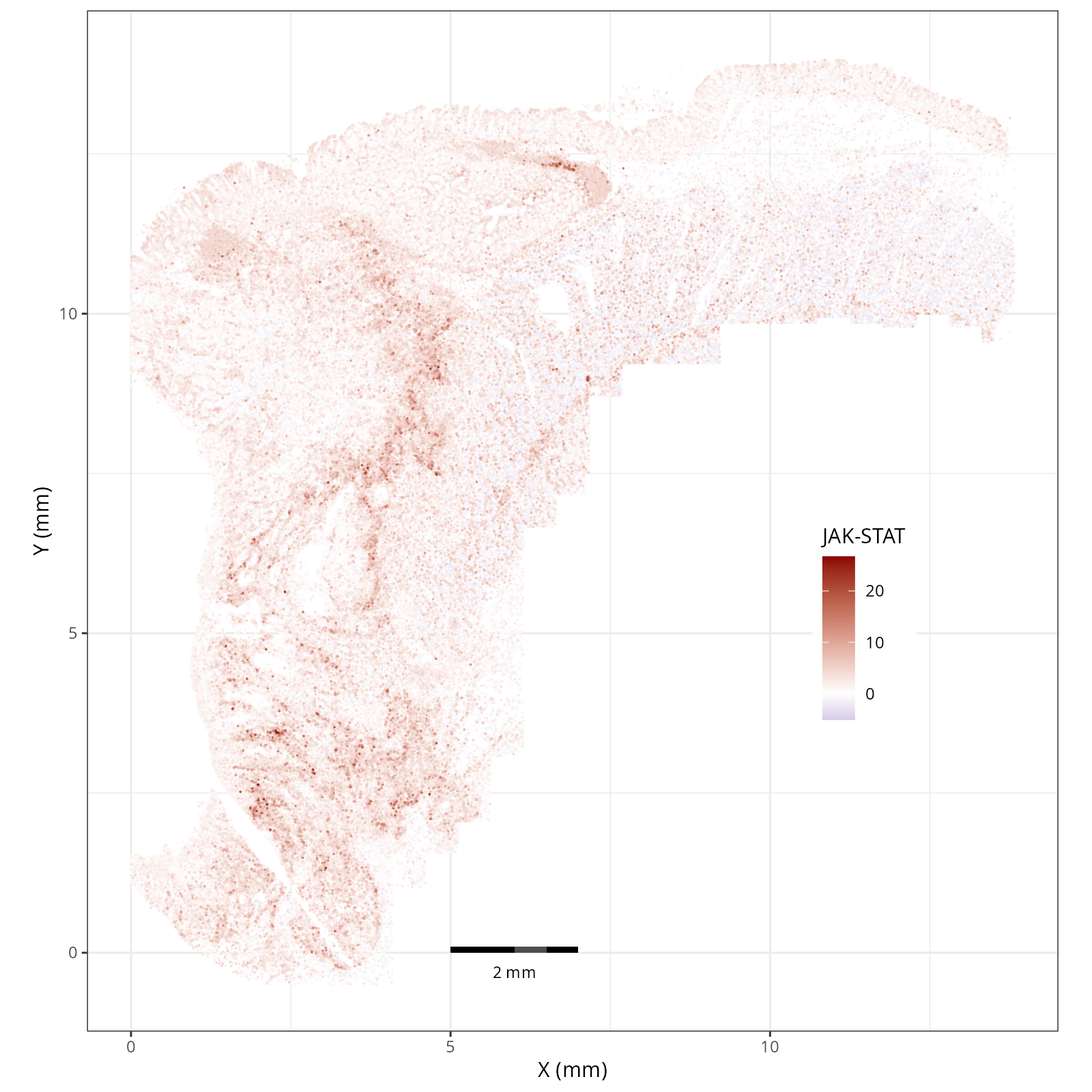

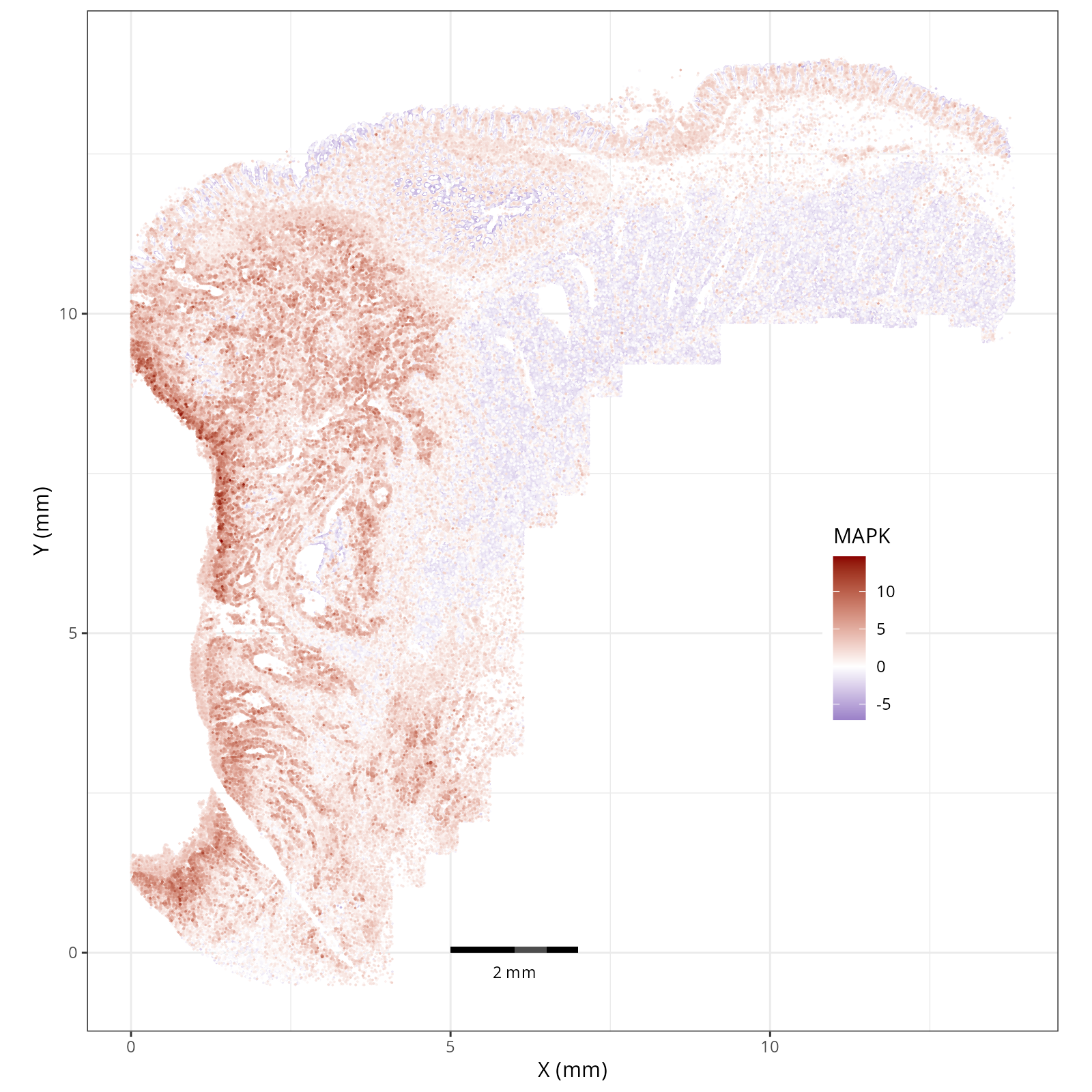

### Local: spatial visualizations {#sec-local-path-plots}

The local plots provide fine-resolution maps of pathway scores on the tissue.

The simplest way to do this is to use scanpy's `pl.spatial` method. If you want

greater flexibility in the plotting aesthetics, we can use the `plotDots` function

in R that we have used throughout this book. Below we'll show code and results

for both approaches.

::: {.panel-tabset}

#### Using Scanpy's built-in spatial plotting function

We can convert the scores themselves into a new annData object and then use

scanpy's functions to plot the individual pathways (features).

```{python}

#| label: nn-scanp-basic-plots

#| eval: false

#| code-summary: "Python Code"

#| message: false

#| warning: false

#| code-fold: true

sc.settings.figdir = r.pw_dir

sc.settings.set_figure_params(dpi_save=200, frameon=False)

nn_pwdata = dc.pp.get_obsm(adata=adata, key=f'score_ulm')

nn_pwdata.obsm[f'padj_ulm'] = adata.obsm[f'padj_ulm']

for x in nn_pwdata.var_names:

sc.pl.spatial(

nn_pwdata,

color=[x],

cmap='RdBu_r',

vcenter=0,

size=1.5,

spot_size=0.01, show=False,

save="_nn_pathway_Scanpy_" + str(x) + "_xy.png",

alpha_img=1

)

```

::: {.panel-tabset}

```{r}

#| output: asis

#| eval: true

files <- Sys.glob(file.path(pw_dir, "show_nn_pathway_Scanpy_*.png"))

res <- purrr::map_chr(files, \(a_file) {

path = gsub('_xy.png', '', strsplit(basename(a_file), split='show_nn_pathway_Scanpy_')[[1]][2])

label = paste0('Path: ', path)

fig_label = paste0('#| label: fig-', gsub(": ", "-", label), '-scanpy')

fig_cap = paste0('#| fig-cap: \"Local ', path ,' pathway scores plotted with sc.pl.spatial.\"')

knitr::knit_child(text = c(

"##### `r paste0('Path: ', gsub('_xy.png', '', strsplit(basename(a_file), split='show_nn_pathway_Scanpy_')[[1]][2]))`",

"",

"```{r eval=TRUE}",

"#| echo: false",

fig_label,

fig_cap,

"render(file.path(analysis_asset_dir, 'pathways'), basename(a_file), pw_dir, overwrite=TRUE)",

"```",

"",

""

), envir = environment(), quiet = TRUE)

})

cat(res, sep = '\n')

```

:::

#### Using `plotDots` in R

This block runs the `plotDots` function that we have used in previous chapters

on the objects that we create in the previous subsection, `nn_pwdata`.

```{r}

#| label: plotDots-visuals

#| eval: false

#| code-summary: "R Code"

#| message: false

#| warning: false

#| code-fold: true

py$nn_pwdata$obsm['spatial'][,2] <- py$nn_pwdata$obsm['spatial'][,2] * -1 # <1>

features <- py$nn_pwdata$var_names$to_list()

for(feature in features){

plotDots(py$nn_pwdata, color_by=feature,

plot_global = TRUE,

facet_by_group = FALSE,

additional_plot_parameters = list(

geom_point_params = list(

size=0.001

),

scale_bar_params = list(

location = c(5, 0),

width = 2,

n = 3,

height = 0.1,

scale_colors = c("black", "grey30"),

label_nudge_y = -0.3

),

directory = pw_dir,

fileType = "png",

dpi = 200,

width = 8,

height = 8,

prefix=paste0("plotDots_", feature)

),

additional_ggplot_layers = list(

theme_bw(),

scale_color_gradient2(low = "darkblue", mid = "white", high = "darkred", midpoint = 0),

xlab("X (mm)"),

ylab("Y (mm)"),

coord_fixed(),

theme(legend.position = c(0.8, 0.4))

)

)

}

```

1. Flipping the y-axis back.

::: {.panel-tabset}

```{r}

#| output: asis

#| eval: true

files <- Sys.glob(file.path(pw_dir, "plotDots_*__spatial__*.png"))

res <- purrr::map_chr(files, \(a_file) {

path = gsub('plotDots_', '', strsplit(basename(a_file), split='__')[[1]][1])

label = paste0('Path: ', path)

fig_label = paste0('#| label: fig-', gsub(": ", "-", label))

fig_cap = paste0('#| fig-cap: \"Local ', path ,' pathway scores plotted with the plotDots function.\"')

knitr::knit_child(text = c(

"##### `r paste0('Path: ', gsub('plotDots_', '', strsplit(basename(a_file), split='__')[[1]][1]))`",

"",

"```{r eval=TRUE}",

"#| echo: false",

fig_label,

fig_cap,

"render(file.path(analysis_asset_dir, 'pathways'), basename(a_file), pw_dir, overwrite=TRUE)",

"```",

"",

""

), envir = environment(), quiet = TRUE)

})

cat(res, sep = '\n')

```

:::

:::

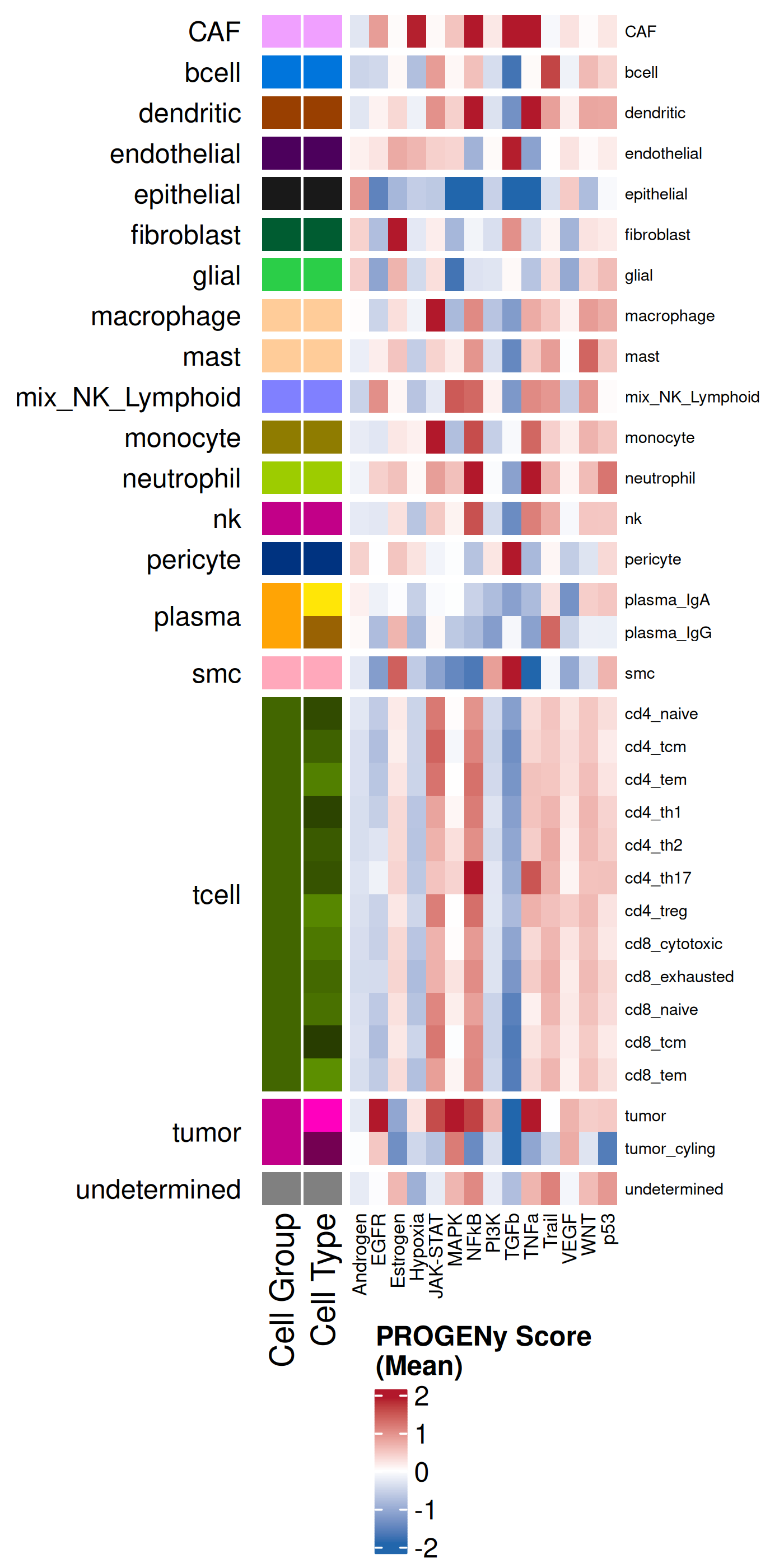

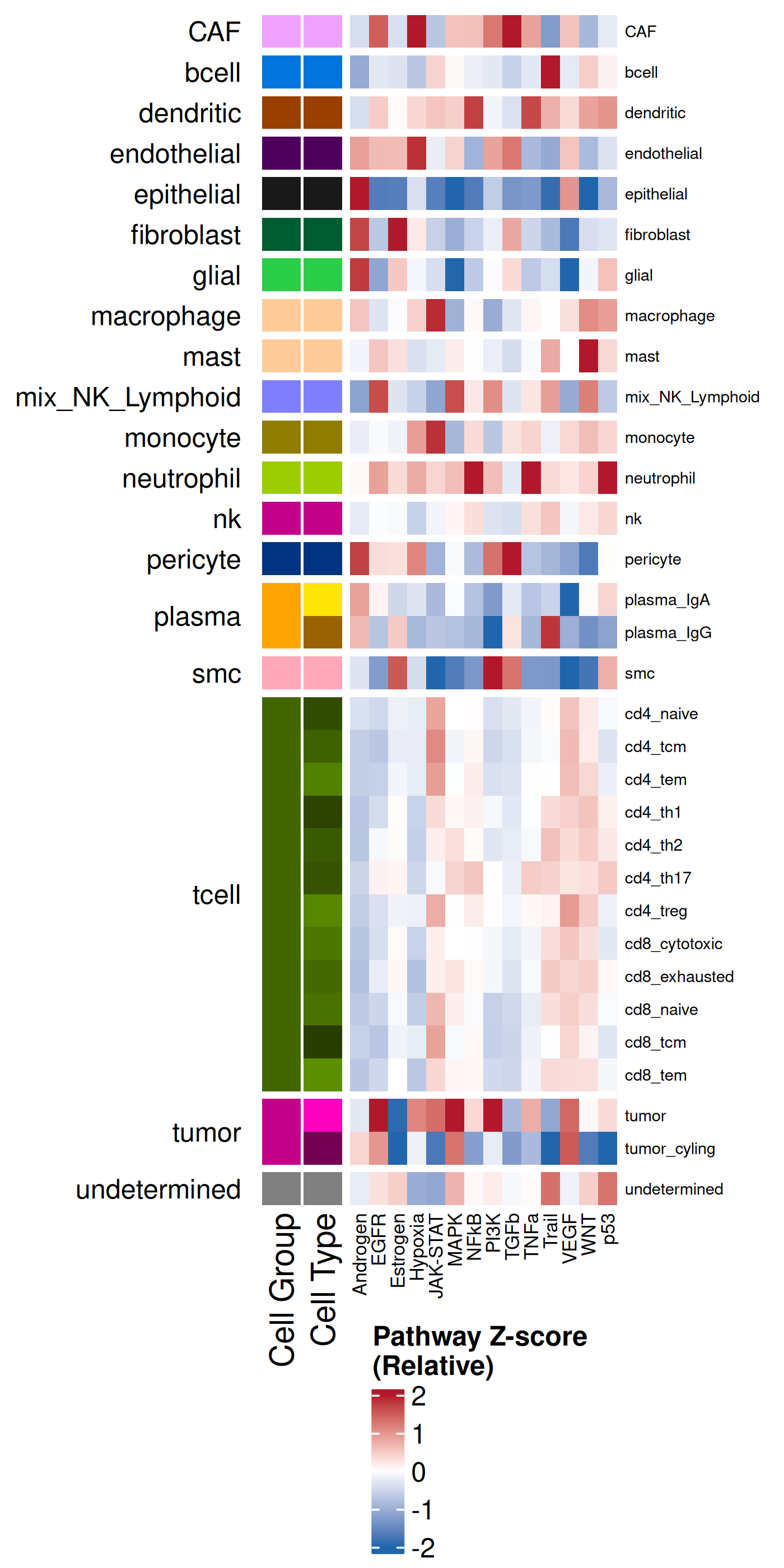

### Global: Per Cell Type

In addition to plotting the local pathway scores in space with scanpy or `plotDots`,

we can visualize the results summarized across each cell type or each domain.

These next two subsections do just that. We'll

use the plotting functionality within the `complexHeatmap` R package. It can be

helpful to plot the average enrichment as well as the Z-scores. The former helps

with us understand the overall sense of what is being enriched whereas the latter

helps to compare a particular effect size relative to other cell types.

```{r}

#| label: celltype-summary

#| eval: false

#| code-summary: "R Code"

#| message: false

#| warning: false

#| code-fold: true

df <- py$nn_pwdata$obs %>% select(cell_ID, celltype_broad, celltype_fine)

expr <- py$nn_pwdata$X

colnames(expr) <- py$nn_pwdata$var_names$to_list()

df <- cbind(df, expr)

pathway_cols <- setdiff(names(df), c("cell_ID", "celltype_broad", "celltype_fine"))

min_obs = 50

mean_enrich_by_ct <- df %>%

group_by(celltype_broad, celltype_fine) %>%

summarise(

n = n(),

across(all_of(pathway_cols), mean, .names = "{.col}_mean"),

.groups = 'drop'

) %>%

filter(n >= min_obs) %>%

arrange(celltype_broad, celltype_fine)

scaled_enrich_by_ct <- mean_enrich_by_ct %>%

mutate(across(ends_with("_mean"), ~as.numeric(scale(.)))) %>%

arrange(celltype_broad, celltype_fine)

celltype_broad_colors <- results_list[['celltype_broad_colors']]

names(celltype_broad_colors) <- results_list[['celltype_broad_names']]

celltype_fine_colors <- results_list[['celltype_fine_colors']]

names(celltype_fine_colors) <- results_list[['celltype_fine_names']]

# Shared Row Annotation

row_ha <- HeatmapAnnotation(

"Cell Group" = scaled_enrich_by_ct$celltype_broad,

"Cell Type" = scaled_enrich_by_ct$celltype_fine,

col = list(

"Cell Group" = celltype_broad_colors,

"Cell Type" = celltype_fine_colors

),

show_legend = c("Cell Group" = FALSE, "Cell Type" = FALSE),

which = "row"

)

zscore_col_fun <- colorRamp2(c(-2, 0, 2), c("#2166AC", "white", "#B2182B"))

heatmap_matrix_z <- scaled_enrich_by_ct %>%

select(ends_with("_mean")) %>%

as.matrix()

rownames(heatmap_matrix_z) <- scaled_enrich_by_ct$celltype_fine

colnames(heatmap_matrix_z) <- gsub("_mean", "", colnames(heatmap_matrix_z))

ht_z <- Heatmap(

heatmap_matrix_z,

name = "Pathway Z-score\n(Relative)",

col = zscore_col_fun,

left_annotation = row_ha,

show_row_names = TRUE,

row_names_gp = gpar(fontsize = 6),

cluster_columns = FALSE, # <1>

column_names_gp = gpar(fontsize = 7),

row_split = scaled_enrich_by_ct$celltype_broad,

cluster_row_slices = TRUE,

cluster_rows = FALSE,

row_title_rot = 0,

row_title_gp = gpar(fontsize = 10)

)

svglite::svglite(file.path(pw_dir, "heatmap_by_cell_type_zscore.svg"), width = 3.5, height = 6)

draw(

ht_z,

heatmap_legend_side = "bottom",

annotation_legend_side = "bottom",

merge_legend = TRUE

)

dev.off()

png(file.path(pw_dir, "heatmap_by_cell_type_zscore.png"),

width=4, height=8, res=350, units = "in", type = 'cairo')

draw(

ht_z,

heatmap_legend_side = "bottom",

annotation_legend_side = "bottom",

merge_legend = TRUE

)

dev.off()

heatmap_matrix_mean <- mean_enrich_by_ct %>%

select(ends_with("_mean")) %>%

as.matrix()

rownames(heatmap_matrix_mean) <- mean_enrich_by_ct$celltype_fine

colnames(heatmap_matrix_mean) <- gsub("_mean", "", colnames(heatmap_matrix_mean))

quantile_limit <- 0.95

limit <- as.numeric(quantile(abs(as.vector(heatmap_matrix_mean)), quantile_limit, na.rm = TRUE))

mean_col_fun <- colorRamp2(c(-limit, 0, limit), c("#2166AC", "white", "#B2182B"))

ht_mean <- Heatmap(

heatmap_matrix_mean,

name = "PROGENy Score\n(Mean)",

col = mean_col_fun,

left_annotation = row_ha,

show_row_names = TRUE,

row_names_gp = gpar(fontsize = 6),

cluster_columns = FALSE,

column_names_gp = gpar(fontsize = 7),

row_split = mean_enrich_by_ct$celltype_broad,

cluster_row_slices = TRUE,

cluster_rows = FALSE,

row_title_rot = 0,

row_title_gp = gpar(fontsize = 10)

)

svglite::svglite(file.path(pw_dir, "heatmap_by_cell_type_mean.svg"), width = 3.5, height = 6)

draw(

ht_mean,

heatmap_legend_side = "bottom",

annotation_legend_side = "bottom",

merge_legend = TRUE

)

dev.off()

png(file.path(pw_dir, "heatmap_by_cell_type_mean.png"),

width=4, height=8, res=350, units = "in", type = 'cairo')

draw(

ht_mean,

heatmap_legend_side = "bottom",

annotation_legend_side = "bottom",

merge_legend = TRUE

)

dev.off()

```

1. Set to FALSE to make it easier to compare the mean and the Z-score heatmaps. Set to TRUE to make it easier to group similar pathway signatures.

::: {.panel-tabset}

#### Mean

```{r}

#| label: fig-heatmap-paths-by-celltypes-m

#| eval: true

#| echo: false

#| code-summary: "R Code"

#| fig-cap: "Average pathway enrichment scores by cell type."

#| fig-align: center

#| out-width: "70%"

render(file.path(analysis_asset_dir, 'pathways'), "heatmap_by_cell_type_mean.png", source_parent_folder=pw_dir, overwrite=TRUE)

```

#### Z-score

```{r}

#| label: fig-heatmap-paths-by-celltypes-z

#| eval: true

#| echo: false

#| code-summary: "R Code"

#| fig-cap: "Average pathway enrichment scores (z-score) by cell type."

#| fig-align: center

#| out-width: "70%"

render(file.path(analysis_asset_dir, 'pathways'), "heatmap_by_cell_type_zscore.png", source_parent_folder=pw_dir, overwrite=TRUE)

```

:::

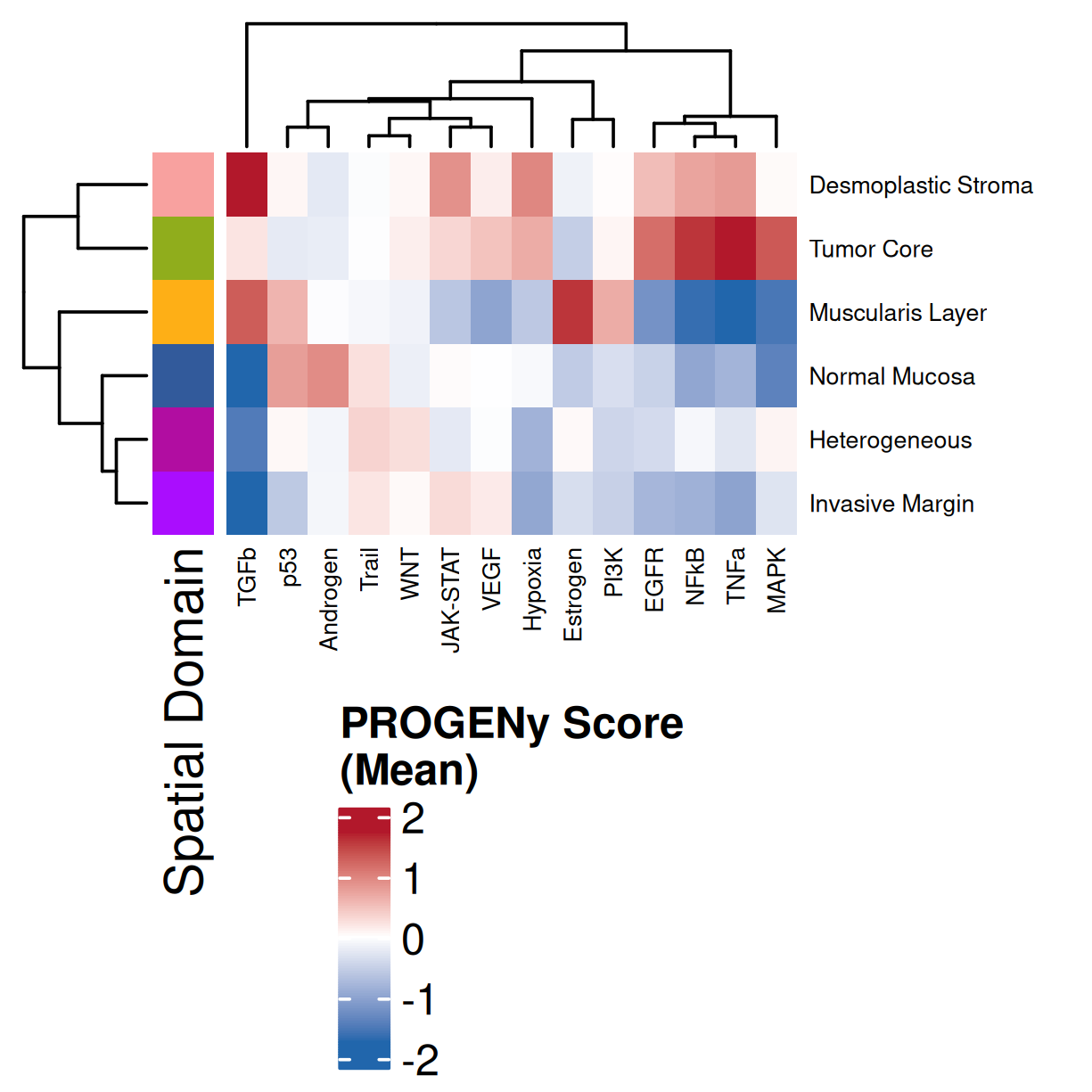

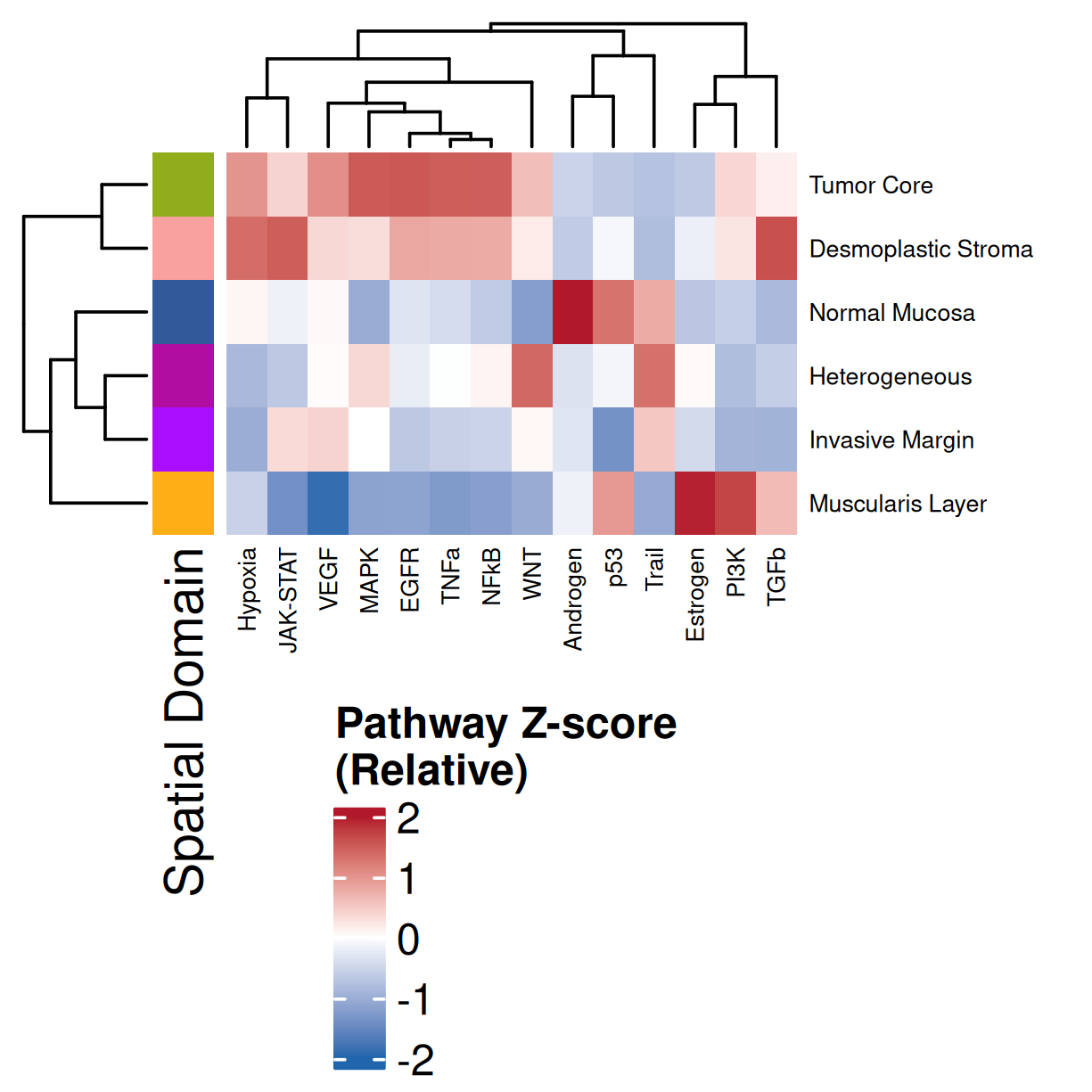

### Global: Per Domain

This follows a similar procedure as above but summarized across spatial domains.

```{r}

#| label: domain-summary

#| eval: false

#| code-summary: "R Code"

#| message: false

#| warning: false

#| code-fold: true

df <- merge(df, py$nn_pwdata$obs %>% select(cell_ID, annotated_domain), by="cell_ID")

df <- filter(df, !is.na(annotated_domain))

min_obs = 50

# Calculate Mean Scores

mean_enrich_by_domain <- df %>%

group_by(annotated_domain) %>%

summarise(

n = n(),

across(all_of(pathway_cols), mean, .names = "{.col}_mean"),

.groups = 'drop'

) %>%

filter(n >= min_obs, !is.na(annotated_domain)) %>%

arrange(annotated_domain)

# Calculate Z-scores (Scale the means)

scaled_enrich_by_domain <- mean_enrich_by_domain %>%

mutate(across(ends_with("_mean"), ~as.numeric(scale(.)))) %>%

arrange(annotated_domain)

# Colors

domain_colors_df <- results_list[['domain_colors']]

domain_colors <- domain_colors_df$domain_color

names(domain_colors) <- domain_colors_df$domain_description

# Common Row Annotation

row_ha <- HeatmapAnnotation(

"Spatial Domain" = mean_enrich_by_domain$annotated_domain,

col = list("Spatial Domain" = domain_colors),

show_legend = c("Spatial Domain" = FALSE),

which = "row"

)

# Color Functions

zscore_col_fun <- colorRamp2(c(-2, 0, 2), c("#2166AC", "white", "#B2182B"))

# Z-Score Heatmap

heatmap_matrix_z <- scaled_enrich_by_domain %>%

select(ends_with("_mean")) %>%

as.matrix()

rownames(heatmap_matrix_z) <- scaled_enrich_by_domain$annotated_domain

colnames(heatmap_matrix_z) <- gsub("_mean", "", colnames(heatmap_matrix_z))

ht_z <- Heatmap(

heatmap_matrix_z,

name = "Pathway Z-score\n(Relative)",

col = zscore_col_fun,

left_annotation = row_ha,

show_row_names = TRUE,

row_names_gp = gpar(fontsize = 5.5),

cluster_columns = TRUE,

column_names_gp = gpar(fontsize = 5.5),

row_title_rot = 0,

row_title_gp = gpar(fontsize = 8)

)

svglite::svglite(file.path(pw_dir, "heatmap_by_domain_zscore.svg"), width = 3.5, height = 3)

draw(ht_z, heatmap_legend_side = "bottom", annotation_legend_side = "bottom", merge_legend = TRUE)

dev.off()

png(file.path(pw_dir, "heatmap_by_domain_zscore.png"), width=3.5, height=3.5, res=350, units = "in", type = 'cairo')

draw(ht_z, heatmap_legend_side = "bottom", annotation_legend_side = "bottom", merge_legend = TRUE)

dev.off()

# Mean Score Heatmap

heatmap_matrix_mean <- mean_enrich_by_domain %>%

select(ends_with("_mean")) %>%

as.matrix()

rownames(heatmap_matrix_mean) <- mean_enrich_by_domain$annotated_domain

colnames(heatmap_matrix_mean) <- gsub("_mean", "", colnames(heatmap_matrix_mean))

quantile_limit <- 0.95

limit <- as.numeric(quantile(abs(as.vector(heatmap_matrix_mean)), quantile_limit, na.rm = TRUE))

mean_col_fun <- colorRamp2(c(-limit, 0, limit), c("#2166AC", "white", "#B2182B"))

ht_mean <- Heatmap(

heatmap_matrix_mean,

name = "PROGENy Score\n(Mean)",

col = mean_col_fun,

left_annotation = row_ha,

show_row_names = TRUE,

row_names_gp = gpar(fontsize = 5.5),

cluster_columns = TRUE,

column_names_gp = gpar(fontsize = 5.5),

row_title_rot = 0,

row_title_gp = gpar(fontsize = 8)

)

svglite::svglite(file.path(pw_dir, "heatmap_by_domain_mean.svg"), width = 3.5, height = 3)

draw(ht_mean, heatmap_legend_side = "bottom", annotation_legend_side = "bottom", merge_legend = TRUE)

dev.off()

png(file.path(pw_dir, "heatmap_by_domain_mean.png"), width=3.5, height=3.5, res=350, units = "in", type = 'cairo')

draw(ht_mean, heatmap_legend_side = "bottom", annotation_legend_side = "bottom", merge_legend = TRUE)

dev.off()

```

::: {.panel-tabset}

#### Mean

```{r}

#| label: fig-heatmap-paths-by-domains-m

#| eval: true

#| echo: false

#| code-summary: "R Code"

#| fig-cap: "Average pathway enrichment scores by spatial domain. Colors correspond to domains in @fig-xy-domains. Note: columns were clustered and so will have a difference order than that found in @fig-heatmap-paths-by-domains-z."

#| fig-align: center

#| out-width: "70%"

render(file.path(analysis_asset_dir, 'pathways'), "heatmap_by_domain_mean.png",

source_parent_folder=pw_dir, overwrite=TRUE)

```

#### Z-score

```{r}

#| label: fig-heatmap-paths-by-domains-z

#| eval: true

#| echo: false

#| code-summary: "R Code"

#| fig-cap: "Average pathway enrichment scores (z-score) by spatial domain. Colors correspond to domains in @fig-xy-domains. Note: columns were clustered and so will have a difference order than that found in @fig-heatmap-paths-by-domains-m."

#| fig-align: center

#| out-width: "70%"

render(file.path(analysis_asset_dir, 'pathways'), "heatmap_by_domain_zscore.png",

source_parent_folder=pw_dir, overwrite=TRUE)

```

:::

Examining and comparing the spatial plots in @sec-local-path-plots with the

global heatmaps @fig-heatmap-paths-by-celltypes-m,

@fig-heatmap-paths-by-celltypes-z,

@fig-heatmap-paths-by-domains-m, and

@fig-heatmap-paths-by-domains-z reveals several findings in this tissue.

For example:

- In the tumor cells we see little enrichment of the

pro-apoptotic TRAIL pathway (mean = 0.0; Z-score = -1.1) but high EGFR

enrichment (mean = 2.6; Z-score = 3.7), a pattern associated with increased cell

invasion and metastasis @Sasaki2013.

- Tumor cells are likely a "CMS4" or mesenchymal colon cancer phenotype. The three signatures of this phenotype are 'prominent transforming growth factor–β activation, stromal invasion and angiogenesis' @Guinney2015. Looking at growth regulation, tumor cells themsevles show little enrichment of TGF-$\beta$ (mean = -2.3; Z-score = -0.85); however, the CAFs show the highest levels in the dataset (mean = 7.0; Z-score = 3.9). This pattern mirrors the TGF-$\beta$ exclusion phenotype described in the literature, where stromal activation drives poor prognosis in colon cancer @Calon2015 @Ma2024. For stromal invasion, we can see from the spatial plots both at the cell type-level @fig-xy-celltype-broad and the domain-level (@fig-xy-domains) that CAFs and tumors are found in interdigitated domains. And finally, we found a signature of angiogenesis in tumor cells and tumor and stromal domains with the enrichment of VEGF @Duffy2004.

- There is a strong enrichment of TNF-$\alpha$ and NF-$\kappa$B on the left side

of the tissue that is still unresolved. The left side of the tissue is part of the

"Heterogeneous" spatial domain that is found throughout (@sec-domains) that contains

a high proportion of undetermined cell types (@fig-contingency-table). Perhaps

a follow up analysis would include isolating the cells within this "sub-domain"

to understand which cells might be driving the reduction of apoptosis and preventing

an effective immune response. This could be done with lasso selecting the region

(see our [blog post on lasso selecting with napari](https://nanostring-biostats.github.io/CosMx-Analysis-Scratch-Space/posts/napari-rois/cosmx-rois.html){target="_blank"}).

## Summary

In this chapter, we showed a simple nearest-neighbor smoothing technique and

scored pathways using one of the available databases (PROGENy; for others see

`decoupler.op.show_resources()`). Then we showed a few ways to pivot the data

and visualize the local scores or global aggregates these scores across cell types

and spatial domains to guide our inference.