---

subtitle: Pre-processing – From Counts to Clusters

author:

- name: Evelyn Metzger

orcid: 0000-0002-4074-9003

affiliations:

- ref: bsb

- ref: eveilyeverafter

execute:

eval: true

freeze: auto

message: true

warning: false

self-contained: false

code-fold: false

code-tools: true

code-annotations: hover

engine: knitr

prefer-html: true

format: live-html

webr:

packages:

- dplyr

- duckdb

repos:

- https://r-lib.r-universe.dev

resources:

- assets/interactives/umap_explore.parquet

- assets/interactives/umap_explore_qc_flags.parquet

---

{{< include ./_extensions/r-wasm/live/_knitr.qmd >}}

# Normalization, Reduction, and Clustering {#sec-preprocessing}

```{r}

#| label: Preamble

#| eval: true

#| echo: true

#| message: false

#| code-fold: true

#| code-summary: "R code"

source("./preamble.R")

reticulate::source_python("./preamble.py")

analysis_dir <- file.path(getwd(), "analysis_results")

input_dir <- file.path(analysis_dir, "input_files")

output_dir <- file.path(analysis_dir, "output_files")

analysis_asset_dir <- "./assets/analysis_results" # <1>

qc_dir <- file.path(output_dir, "qc")

if(!dir.exists(qc_dir)){

dir.create(qc_dir, recursive = TRUE)

}

pp_dir <- file.path(output_dir, "processing")

if(!dir.exists(pp_dir)){

dir.create(pp_dir, recursive = TRUE)

}

results_list_file = file.path(analysis_dir, "results_list.rds")

if(!file.exists(results_list_file)){

results_list <- list()

saveRDS(results_list, results_list_file)

} else {

results_list <- readRDS(results_list_file)

}

source("./helpers.R") # contains the plotDots function

```

Our quality control steps in @sec-quality-processing identified the analyzable

cells, but these their raw counts need further processing to reveal biological

patterns. This chapter covers the essential pre-processing steps to make the

data interpretable.

First, normalization adjusts counts to account for technical factors like cell

area (_i.e._, larger cells typically have more counts), enabling fair comparisons

between cells. Second, dimensionality reduction (using PCA and UMAP) helps

reduce the total number of dimensions in the data (almost 19,000) to a

manageable representation that captures key biological variation and allows

visualization. Finally, clustering leverages this reduced space to group cells

with similar expression profiles, which can be a foundation for downstream

analyses like cell typing.

By the end of this chapter, we will have transformed the filtered count matrix

into a clustered, low-dimensional dataset and classified cells into groups which,

taken together, form our foundation for

biological interpretation and spatial analysis. I often get asked "What is the

best parameter combination for CosMx data?" and I hope by the end of this chapter

you're able to understand how parameter adjustments impact many of these processing

steps.

Let's begin by loading the data.

```{python}

#| label: load-anndata

#| eval: false

#| code-summary: "Python Code"

#| message: true

#| warning: false

#| code-fold: show

adata = ad.read_h5ad(os.path.join(r.analysis_dir, "anndata-1-qc-filtered.h5ad"))

```

## Two pre-processing workflows

There are two different pre-processing workflows that I use. The first one

is borrowed from spatially-unaware scRNA-seq. The

main advantage of this approach is that it is fast, the normalization matrix can

remain sparse, the values are easy to understand (_e.g.,_ counts of gene X per 10,000 or

some transformation of such), and often times for WTX data provides the basis for good clustering

of cells in downstream UMAP. Moreover, Scanpy and Seurat each have built-in methods

for these steps which make it relatively low friction. However, there are cases were

this standard ("legacy") workflow provides unexpected results. One reason is that total

counts-based normalization might have unstable variance @Hafemeister2019 such that

high-expressing housekeeping genes might have high variance and disproportionately

effect downstream dimensional reduction and clustering.

The second, newer

workflow that I have been using is based on normalization using Pearson Residuals (PR).

The approach itself is not new and scanpy has a built-in method for it

(_i.e._, `scanpy.experimental.pp.normalize_pearson_residuals`).

Until recently the main disadvantage for using PR

is that it doesn't scale well to large number of cells that are typical in CosMx SMI[^1]

and it creates a large, dense normalization matrix that can make analysis and read/writing

slower. Fortunately, in many cases I do not need to compute and store such a dense

matrix. For example, Dan McGuire recently created the R package

[scPearsonPCA](https://nanostring-biostats.github.io/CosMx-Analysis-Scratch-Space/posts/pearsonpca)

that can estimate the Principle Components (PCs) of the PR normalized data

without needing to convert and use very dense matrices (which we will show below).

While this workflow involves converting data between python and R, I generally

find the clusters that are derived from such data are comparable to the standard

workflow or superior and so I recommend this workflow overall.

In this chapter, I'll run both the standard and recommended workflows on the colon

cancer dataset to provide code for both approaches. I will also do a deep-dive

on the choice of UMAP parameters.

This particular dataset is a case where the results are more-or-less

comparable and I'll pick the PR data to use throughout the rest of the colon

analysis.

Let's begin. Both options begin the same way: computing the highly variable genes (HVGs).

I have found that the `pearson_residulas` method to

detect HVGs (not to be confused with PR normalization) provides stable results for a variety of CosMx

SMI WTX experiments.

```{python}

#| label: RNA-preprocessing

#| eval: false

#| code-summary: "Python Code"

#| message: false

#| warning: false

#| code-fold: show

adata.layers["counts"] = adata.X.copy()

sc.experimental.pp.highly_variable_genes( # <1>

adata,

flavor='pearson_residuals',

n_top_genes=4000, # <2>

layer='counts'

)

```

1. the pearson_residuals 'flavor' implement in this function is not the same as the

pearson residuals _normalization method_ (see below).

2. generally 3000-5000 is a good starting point here.

::: {.column-margin}

::: {.otherapproachesbox title="Alternative Approach"}

The pre-processing workflow presented here can be considered a good overall

starting point towards understanding the structure of the data.

As such I have omitted more complex workflows and tasks such

as integrating morphology-based and/or protein-based PCs into the analysis. For

a more involved workflow, see our upcoming WTX paper.

:::

:::

The tabs below show both of these workflows. In each workflow, I set the umap

parameters to be identical (40 PCs, 15 nearest neighbors, spread = 2 and minimum

distance = 0.02). While these are fixed here, see the box `Choosing UMAP Parameters`

below to see how these

parameters effect the UMAP visual and the Leiden cluster assignments.

::: {.panel-tabset}

### Total Counts Workflow {#sec-tc-workflow}

> Workflow: Total counts-based normalization > log transformation > PCA

The procedure below adapts a standard `scanpy` [pipeline](https://scanpy.readthedocs.io/en/stable/tutorials/basics/clustering.html#normalization).

We'll first normalize each

cell the median total counts

and then log tranform the data.

With this approach I find that scaling the log1p data tends to generate more distinct

and biologically relevant clusters so I add that step.

Thus, we'll focus our analysis on the most variable

genes found in the dataset. After subsetting down to only these 4000 HVGs, we'll scale

each gene, run PCA, and put these HVG-derivied PCs into the full annData object.

On this dataset (`r results_list$n_cells_after_qc` cells), this whole process took

about a minute.

```{python}

#| label: TC-1

#| eval: false

#| code-summary: "Python Code"

#| message: false

#| warning: false

#| code-fold: show

sc.pp.normalize_total(adata)

sc.pp.log1p(adata) # -> adata.X

adata.layers['TC'] = adata.X.copy()

# Subset to HVGs and get PCs

adata_hvg = adata[:, adata.var.highly_variable].copy()

sc.pp.scale(adata_hvg) # -> adata.X

sc.tl.pca(adata_hvg, svd_solver='auto')

adata.obsm['X_pca_TC'] = adata_hvg.obsm['X_pca']

```

Run UMAP and Leiden with the top 40 PCs.

```{python}

#| label: TC-2

#| eval: false

#| code-summary: "Python Code"

#| message: false

#| warning: false

#| code-fold: show

sc.pp.neighbors(adata, n_neighbors=15, n_pcs=40, metric = 'cosine',

use_rep='X_pca_TC', key_added='neighbors_TC')

UMAP = sc.tl.umap(adata, min_dist=0.02, spread=2, neighbors_key='neighbors_TC', copy=True)

adata.obsm['umap_TC'] = UMAP.obsm['X_umap']

adata.uns['umap_TC_params'] = UMAP.uns['umap']

sc.tl.leiden(adata, resolution=0.5,

key_added='leiden_tc', flavor='igraph',

n_iterations=2, neighbors_key='neighbors_TC')

```

### Pearson Residuals Workflow

> Workflow: Py to R > scPearsonPCA

The `scPearsonPCA` package estimates the PCs of the PR data without computing

and storing a dense normalized matrix.

Since it is written in R, we'll add it to this workflow

via `reticulate` after converting a few objects.

```{python}

#| label: PR-1

#| eval: false

#| code-summary: "Python Code"

#| message: false

#| warning: false

#| code-fold: show

total_counts_per_cell = adata.layers['counts'].sum(axis=1)

total_counts_per_cell = np.asarray(total_counts_per_cell).flatten()

total_counts_per_target = adata.layers['counts'].sum(axis=0)

total_counts_per_target = np.asarray(total_counts_per_target).flatten()

target_frequencies = total_counts_per_target / total_counts_per_target.sum()

adata_hvg = adata[:, adata.var.highly_variable].copy()

hvgs_counts = adata_hvg.layers['counts'].copy().astype(np.int64)

```

Convert relevant data to R.

```{r}

#| label: PR-2

#| eval: false

#| code-summary: "R Code"

#| message: true

#| warning: false

#| code-fold: show

library(Matrix)

hvgs_counts <- py$hvgs_counts

rownames(hvgs_counts) <- py$adata_hvg$obs_names$to_list()

colnames(hvgs_counts) <- py$adata_hvg$var_names$to_list()

# the approach we use below expects a sparse matrix with genes (rows) by cells (columns)

t_hvgs_counts <- Matrix::t(hvgs_counts)

t_hvgs_counts <- as(t_hvgs_counts, "CsparseMatrix")

```

Install the scPearsonPCA package (and remotes), if needed.

```{r}

#| label: PR-3

#| eval: false

#| code-summary: "R Code"

#| message: true

#| warning: false

#| code-fold: show

remotes::install_github("Nanostring-Biostats/CosMx-Analysis-Scratch-Space",

subdir = "_code/scPearsonPCA", ref = "Main")

```

Run Seurat-style PCA using scPearsonPCA.

```{r}

#| label: PR-4

#| eval: false

#| code-summary: "R Code"

#| message: true

#| warning: false

#| code-fold: show

library(scPearsonPCA)

total_counts_per_cell <- py$total_counts_per_cell

target_frequencies <- py$target_frequencies

names(target_frequencies) <- py$adata$var_names$to_list()

pcaobj <- sparse_quasipoisson_pca_seurat(

x = t_hvgs_counts,

totalcounts = total_counts_per_cell,

grate = target_frequencies[rownames(t_hvgs_counts)],

scale.max = 10,

do.scale = TRUE,

do.center = TRUE,

ncores = 5

)

pca <- pcaobj$reduction.data@cell.embeddings

```

Add these PCs to the annData object in Python. Run UMAP and Leiden with the top 40 PCs.

```{python}

#| label: PR-6

#| eval: false

#| code-summary: "Python Code"

#| message: false

#| warning: false

#| code-fold: show

adata.obsm["X_pca_pr"] = r.pca

sc.pp.neighbors(adata, n_neighbors=15, n_pcs=40, metric = 'cosine',

use_rep='X_pca_pr', key_added='neighbors_pr')

UMAP = sc.tl.umap(adata, min_dist=0.02, spread=2, neighbors_key='neighbors_pr', copy=True)

adata.obsm['umap_pr'] = UMAP.obsm['X_umap']

adata.uns['umap_pr_params'] = UMAP.uns['umap']

sc.tl.leiden(adata, resolution=0.5,

key_added='leiden_pr', flavor='igraph',

n_iterations=2, neighbors_key='neighbors_pr')

```

:::

Save the annData object.

```{python}

#| label: save-anndata

#| eval: false

#| code-summary: "Python Code"

#| message: false

#| warning: false

#| code-fold: show

adata.write_h5ad(

os.path.join(r.analysis_dir, "anndata-2-leiden.h5ad"),

compression=hdf5plugin.FILTERS["zstd"],

compression_opts=hdf5plugin.Zstd(clevel=5).filter_options

)

```

## Visualizations

Now that we have the UMAP embeddings and the Leiden cluster assignments in the

annData object, we can plot the results of the two methods and compare.

The easiest way to plot the Leiden clusters in UMAP space is with scnapy's built-in

method, [`sc.pl.umap`](https://scanpy.readthedocs.io/en/stable/generated/scanpy.tl.umap.html); however, since we have non-typical `obsm` keys, we'll use the

more generic [`sc.pl.embedding`](https://scanpy.readthedocs.io/en/latest/api/generated/scanpy.pl.embedding.html) method.

```{python}

#| label: make-umap-figs

#| code-summary: "Python Code"

#| code-fold: show

#| message: false

#| warning: false

#| echo: true

#| eval: false

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

sc.settings.figdir = r.pp_dir

save_dir = r.pp_dir

adata.obs['log10_nCount_RNA'] = np.log10(adata.obs['nCount_RNA'] + 1)

adata.obs['qcflag'] = adata.obs['qcflag'].astype('category')

fig, ((ax1, ax2), (ax3, ax4), (ax5, ax6)) = plt.subplots(3, 2, figsize=(15, 10))

sc.pl.embedding(adata,

basis='umap_TC',

color='leiden_tc',

title='Total Counts (leiden_tc)',

palette=sc.pl.palettes.default_20,

ax=ax1,

show=False)

sc.pl.embedding(adata,

basis='umap_pr',

color='leiden_pr',

title='Pearson Residuals (leiden_pr)',

palette=sc.pl.palettes.default_20,

ax=ax2,

show=False)

sc.pl.embedding(adata,

basis='umap_TC',

color='log10_nCount_RNA',

title='Total Counts (log10_nCount_RNA)',

ax=ax3,

show=False)

sc.pl.embedding(adata,

basis='umap_pr',

color='log10_nCount_RNA',

title='Pearson Residuals (log10_nCount_RNA)',

ax=ax4,

show=False)

sc.pl.embedding(adata,

basis='umap_TC',

color='qcflag',

title='Total Counts (FOV QC Flag)',

palette=sc.pl.palettes.default_20,

ax=ax5,

show=False)

sc.pl.embedding(adata,

basis='umap_pr',

color='qcflag',

title='Pearson Residuals (FOV QC Flag)',

palette=sc.pl.palettes.default_20,

ax=ax6,

show=False)

plt.tight_layout()

filename = "umap_umap_compare.png"

save_path = os.path.join(save_dir, filename)

plt.savefig(save_path)

```

```{r}

#| label: fig-umap-leiden-simple

#| message: false

#| warning: false

#| echo: false

#| fig.width: 8

#| fig.height: 12

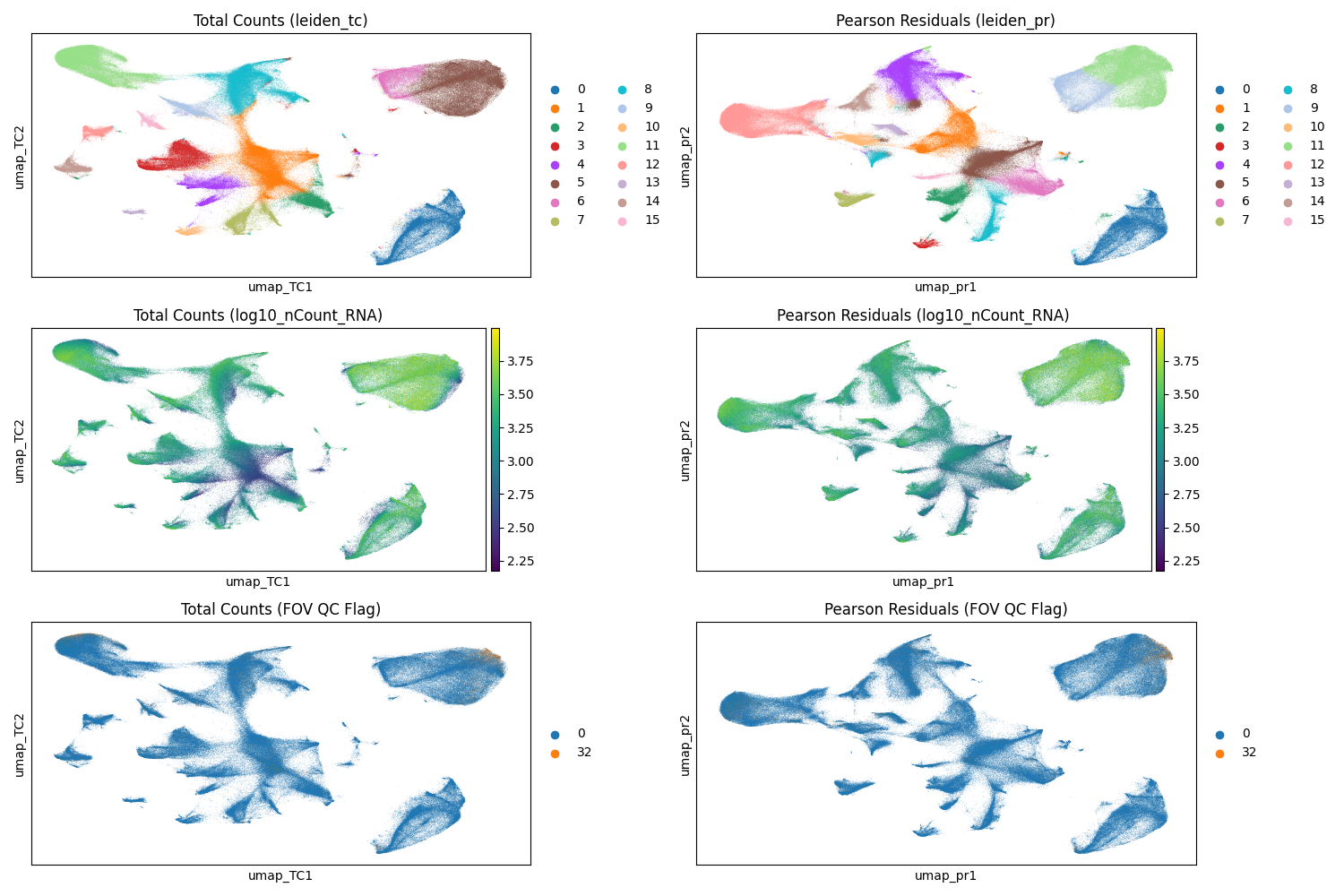

#| fig-cap: "UMAP with Leiden clusters from total counts normalization (left) and scPearsonPCA PCs (right). Note that a given cluster label in one plot is not the same as that label in the other plot. Top: Leiden clusters. Middle: cells colored by their total counts. Bottom: cells colored by their QC flag (0 = no flag; 32 = FOV flag; no other flaggeed cells were processed)."

#| eval: true

render(file.path(analysis_asset_dir, "preprocessing"), "umap_umap_compare.png", pp_dir, overwrite=TRUE)

```

Both normalization methods demonstrate effective cluster separation

(@fig-umap-leiden-simple). When evaluating these visualizations, it is important

to watch for artifacts, particularly sub-clustering driven primarily by total

transcript counts, which can signal suboptimal normalization. Additionally,

because we retained cells flagged by FOV QC (flag 32), we must verify that these

cells do not aggregate into spurious "satellite" clusters which could

indicate technical artifacts rather than biological signal. In this dataset,

while FOV QC-flagged cells are present in the upper right cluster (Leiden 5 in

the total counts workflow and Leiden 11 in the Pearson Residuals workflow), they

do not form a distinct artifactual group. Instead, they appear integrated with

the dominant cell population, suggesting their distribution is driven by the

biology of that region -- a hypothesis we will elucidate further in

@sec-celltyping.

We can compare which combination of Leiden clusters a given cell was assigned to:

```{python}

#| echo: true

#| eval: false

import pandas as pd

import seaborn as sns

crosstab = pd.crosstab(

adata.obs['leiden_tc'],

adata.obs['leiden_pr']

)

crosstab_norm = crosstab.div(crosstab.sum(axis=1), axis=0)

plt.figure(figsize=(12, 10))

sns.heatmap(

crosstab_norm,

annot=True,

fmt=".2f", cmap="viridis",

linewidths=.5

)

plt.title("Comparison of Leiden clusters derived from TC or PR workflows", fontsize=16)

plt.ylabel("Total Counts (leiden_tc)", fontsize=12)

plt.xlabel("Pearson Residuals (leiden_pr)", fontsize=12)

filename = "leiden_compare_crosstab.png"

save_path = os.path.join(save_dir, filename)

plt.savefig(save_path)

```

```{r}

#| label: fig-umap-leiden-compare

#| message: false

#| warning: false

#| echo: false

#| fig.width: 12

#| fig.height: 12

#| fig-cap: "Proportion of cells classified with the pure scanpy-based approach compared to the scPearsonPCA-based appraoch."

#| eval: true

render(file.path(analysis_asset_dir, "preprocessing"), "leiden_compare_crosstab.png", pp_dir, overwrite=TRUE)

```

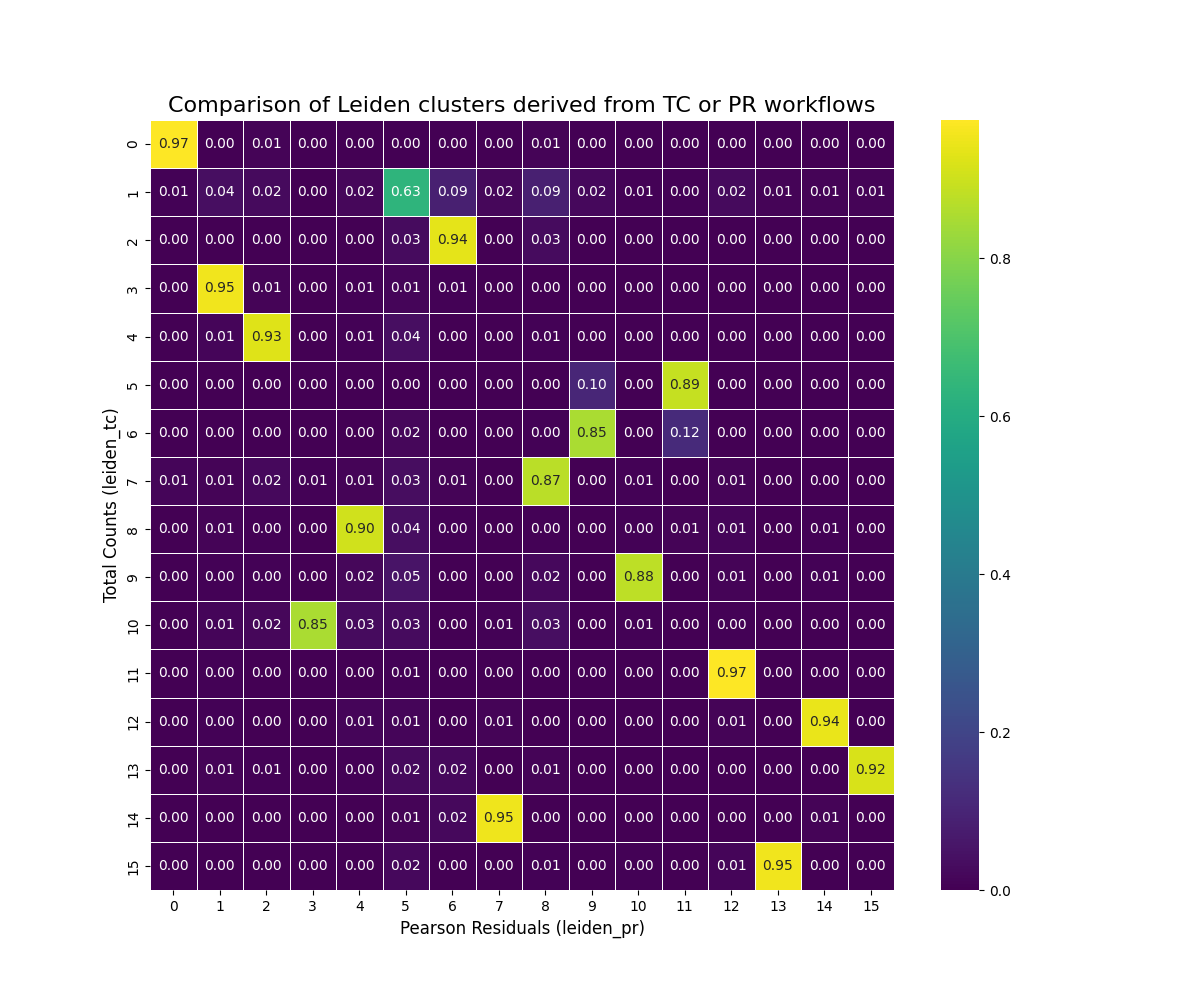

@fig-umap-leiden-compare shows a relationship between the clusters derived

from our two normalization approaches.

Most (15 of 16) Leiden clusters with the total counts

approach have more than 85% of cells that are found in a single Leiden cluster

for the Pearson Residuals method (e.g., 95% of tc_3 cells mapped to pr_1). One

cluster in the total counts approach (tc_1) "split" amongst PR clusters (primarily

clusters pr_5, pr_6, and pr_8).

So which is _better_? With this particular dataset the two approaches are comparable.

For the majority of my CosMx SMI WTX analyses I have found the Pearson

Residual-based normalization to provide more meaningful biological clusters

consistently across datasets so

that might be a good overall recommendation -- especially if you are working within

the R ecosystem. If you are looking for a quick analysis, then the total counts-based

approach may work in many cases.

:::{.column-body-outset}

:::{.noteworthybox title="Choosing UMAP Parameters" collapse="true"}

## Choosing UMAP Parameters

UMAP helps visualize how groups of cells relate to each other in

high-dimensional space. While there isn't one "correct" UMAP layout, some

embeddings are more effective than others at revealing underlying biological

structure. We have seen in this chapter how having choice in normalization

alone (via PCA) can alter the shape of a UMAP plot even when all other parameters

are identical (@fig-umap-leiden-simple).

This section explores how commonly adjusted parameters and inputs other than

the choice of normalization influence the

resulting UMAP visualization, aiming to build intuition for how to tune these

parameters effectively in your dataset.

Let's systematically vary five key factors:

- **The quality filtering applied to the input cells.** Using only high-quality

cells often leads to clearer, tighter clusters representing core biological populations.

If filtering was too stringent then entire cell populations might be unrepresented.

- **The number of Principal Components (PCs) used.** Using a lower number will concetrate

on the strongest axes of variation at the cost of reducing any distinction between

cell subtypes if that distinction is found in higher PCs. Choosing a higher number

of PCs can potentially resolve finer subtypes but also risks incorporating noise,

which might slightly blur cluster boundaries or create small, potentially spurious groupings.

- **The number of nearest neighbors (n_neighbors).** Lower `n_neighbors` tends to

emphasize local cluster separation while higher `n_neigbhors` tends to form broader

clusters.

- **The distance metric (metric).** Defines the rule for calculating "closeness"

between cells. Euclidean measures straight-line distance while cosine measures

the angle between gene expression profiles. Since changing this alters

which cells are considered "neighbors," the parameter can have large impacts on

the global shape. Euclidean is the default many packages but cosine often provides

more biologically meaningful clusters for CosMx SMI data.

- **The minimum distance parameter (min_dist).** Controls how tightly packed points

are within a cluster. Higher values tend to make more diffuse clusters.

- **The spread parameter (spread).** Controls the separation between clusters. Lower

`spread` tends to bring clusters closer together.

This list isn't exhaustive, but varying these while keeping others constant will

illustrate their core effects. To make this exploration computationally

feasible, we will use a representative subsample of 50,000 cells from our

quality-flagged dataset. And to make visualization smooth, we'll only plot at most

500 cells.

Click the radio buttons below to see what effect these parameter have on the UMAP

visualization. Some of these changes are gradual while some dramatically alter

the shape and configuration of the UMAP embeddings. You'll note that filtering out

the poor quality cells doesn't merely remove the cells from the UMAP; instead,

the inclusion of poorer-quality data can effect the entire UMAP topology. I have

also included the Leiden clusters for these cells. The number of PCs and the

number of neighbors effect Leiden cluster cell assignment while `spread` and

`min_dist` do not.

Encouragingly, in this dataset there doesn't appear to be any UMAP clusters that

appear to be made up of cells that were flagged in our FOV QC analysis (@sec-fov-qc). If this

_was_ the case, it would suggest that we would want to remove the cells in the

effected FOVs.

```{python}

#| eval: false

#| echo: false

# This section is for the example only -- not part of a regular analysis

import itertools

import pandas as pd

import numpy as np

import pyarrow as pa

import pyarrow.parquet as pq

import scanpy as sc

import os

bdata = sc.read_h5ad(os.path.join(r.analysis_dir, "anndata-1-qc-flagged.h5ad"))

n_subsample = 50000

random_seed = 98103

sc.pp.subsample(bdata, n_obs=n_subsample, random_state=random_seed)

# Define Parameters

qc_levels = {

"no QC filter": None,

"include FOV QC cells": [0, 32],

"filter all flags": [0]

}

# Graph Parameters (affect the topology/connections)

graph_params = list(itertools.product(

[10, 20, 30, 40, 50], # n_pcs

[15, 30, 50], # n_neighbors

['euclidean', 'cosine'] # metric

))

# Layout Parameters (affect only the visualization)

layout_params = list(itertools.product(

[0.01, 0.05, 0.2, 0.5], # min_dist

[0.5, 1.0, 2.0] # spread

))

all_embeddings_list = []

for qc_level, qc_flags in qc_levels.items():

print(f"--- Starting QC Level: {qc_level} ---")

# Create base object for this QC level

if qc_level != "no QC filter":

adata_qc = bdata[bdata.obs['qcflag'].isin(qc_flags), :].copy()

else:

adata_qc = bdata.copy()

# Preprocessing

adata_qc.layers["counts"] = adata_qc.X.copy()

sc.pp.normalize_total(adata_qc)

sc.pp.log1p(adata_qc)

sc.experimental.pp.highly_variable_genes(

adata_qc, flavor='pearson_residuals', n_top_genes=4000, layer='counts'

)

adata_qc = adata_qc[:, adata_qc.var.highly_variable].copy()

sc.pp.scale(adata_qc)

sc.tl.pca(adata_qc, svd_solver='auto')

for n_pcs, n_neighbors, metric in graph_params:

print(f"----- Starting graph_params: {n_pcs} {n_neighbors} {metric} ---")

adata_graph = adata_qc.copy()

try:

sc.pp.neighbors(

adata_graph,

n_pcs=n_pcs,

n_neighbors=n_neighbors,

use_rep='X_pca',

metric=metric,

random_state=random_seed

)

for min_dist, spread in layout_params:

param_string = f"qc_{qc_level}_pcs_{n_pcs}_nn_{n_neighbors}_met_{metric}_md_{min_dist}_sp_{spread}"

print(f"Running: {param_string}")

sc.tl.umap(adata_graph, min_dist=min_dist, spread=spread, random_state=random_seed)

sc.tl.leiden(adata_graph, resolution=0.5, key_added='leiden', flavor='igraph', n_iterations=2)

embedding_df = pd.DataFrame(

adata_graph.obsm['X_umap'],

index=adata_graph.obs.index,

columns=['umap_1', 'umap_2']

)

# Add metadata

embedding_df['leiden'] = adata_graph.obs['leiden']

embedding_df['qc'] = qc_level

embedding_df['n_pcs'] = n_pcs

embedding_df['n_neighbors'] = n_neighbors

embedding_df['metric'] = metric

embedding_df['min_dist'] = min_dist

embedding_df['spread'] = spread

embedding_df = embedding_df.reset_index().rename(columns={'index': 'cell_id'})

all_embeddings_list.append(embedding_df)

except Exception as e:

print(f"!!! Error params ({n_pcs}, {n_neighbors}, {metric}): {e}")

df = pd.concat(all_embeddings_list, ignore_index=True)

n_subsubsample = 500

random_seed = 98103

umap_output_file = f"./assets/interactives/umap_explore{str(n_subsubsample)}.parquet"

qc_flags_output_file = f"./assets/interactives/umap_explore_qc_flags{str(n_subsubsample)}.parquet"

np.random.seed(random_seed)

unique_cell_ids = df['cell_id'].unique()

cell_ids_pick = np.random.choice(

unique_cell_ids,

size=n_subsubsample,

replace=False

)

cell_ids_pick_set = set(cell_ids_pick)

df_filtered = df[df['cell_id'].isin(cell_ids_pick_set)].copy()

pq.write_table(pa.Table.from_pandas(df_filtered), umap_output_file)

pq.write_table(pa.Table.from_pandas(df_filtered), "./assets/interactives/umap_explore.parquet")

bmeta = bdata.obs.loc[bdata.obs.index.isin(cell_ids_pick_set), ['cell_ID', 'qcflag']].copy()

bmeta['cell_id'] = bmeta.index

bmeta_filtered = bmeta.loc[bmeta['qcflag'] != 0, ['cell_id', 'qcflag']].reset_index(drop=True)

pq.write_table(pa.Table.from_pandas(bmeta_filtered), qc_flags_output_file)

pq.write_table(pa.Table.from_pandas(bmeta_filtered), "./assets/interactives/umap_explore_qc_flags.parquet")

```

:::: {.columns}

::: {.column width="40%"}

```{webr}

#| echo: false

#| eval: true

#| edit: false

#| define:

#| - qc_flags_data

# This block fetches the QC

# flag codes for the cell ids (numeric) so that it can be merged in the plots

# and tables.

qc_flags_file <- "assets/interactives/umap_explore_qc_flags.parquet"

qc_flags_data <- data.frame(cell_id = character(), qcflag = integer())

con <- tryCatch({ dbConnect(duckdb()) }, error = function(e) { print(e); NULL })

if (!is.null(con)) {

if (file.exists(qc_flags_file)) {

# print("Loading QC flags data...")

qc_flags_data <- tryCatch({

dbGetQuery(con, paste0("SELECT * FROM '", qc_flags_file, "'"))

}, error = function(e) {

# print("Error reading QC flags parquet:")

print(e)

qc_flags_data # Return default empty

})

# print(paste("Loaded", nrow(qc_flags_data), "QC flag entries."))

} else {

print(paste("QC flags file not found:", qc_flags_file))

}

dbDisconnect(con, shutdown = TRUE)

}

```

```{ojs}

//| eval: true

//| echo: false

viewof qc_level = Inputs.radio(["no QC filter", "include FOV QC cells", "filter all flags"], {label: "QC Level", value: "include FOV QC cells"})

viewof n_pcs = Inputs.radio([10, 20, 30, 40, 50], {label: "PCs", value: 30})

viewof n_neighbors = Inputs.radio([15, 30, 50], {label: "Neighbors", value: 30})

viewof metric = Inputs.radio(["euclidean", "cosine"], {label: "Metric", value: "cosine"})

viewof mdist = Inputs.radio([0.01, 0.05, 0.2, 0.5], {label: "Min. distance", value: 0.2})

viewof spread = Inputs.radio([0.5, 1.0, 2.0], {label: "Spread", value: 2.0})

viewof colorby = Inputs.radio(["QC", "Leiden"], {label: "Color by", value: "QC"})

```

```{webr}

#| echo: false

#| eval: true

#| edit: false

#| input:

#| - qc_level

#| - n_pcs

#| - n_neighbors

#| - metric

#| - mdist

#| - spread

#| - colorby

#| define:

#| - query_data

# connection to an in-memory DuckDB database.

con <- dbConnect(duckdb())

# build the SQL query

query <- paste0(

"SELECT * FROM 'assets/interactives/umap_explore.parquet' WHERE qc = '",

qc_level,

"' AND n_pcs = '",

n_pcs,

"' AND n_neighbors = '",

n_neighbors,

"' AND metric = '",

metric,

"' AND min_dist = '",

mdist,

"' AND spread = '",

spread, "'"

)

query_data <- tryCatch({

dbGetQuery(con, query)

}, error = function(e) {

print("--- SQL Query Error ---")

print("Query that failed:")

print(query)

print("Error message:")

print(e)

data.frame(

cell_id = character(),

umap_1 = numeric(),

umap_2 = numeric()

)

})

dbDisconnect(con, shutdown = TRUE)

```

<!-- static QC flag legend and defs -->

```{ojs}

//| echo: false

//| eval: true

//| output: false

// Define the meaning of each bit

qcMasks = ({

LOW_COUNTS: 1 << 0,

HIGH_COUNTS: 1 << 1,

LOW_FEAT: 1 << 2,

HIGH_FEAT: 1 << 3,

LOW_SPLIT: 1 << 4,

FOV_QC: 1 << 5,

LOW_SBR: 1 << 6

})

flagNames = Object.keys(qcMasks).sort((a, b) => qcMasks[a] - qcMasks[b]);

qcFlagMap = new Map(qc_flags_data.map(d => [d.cell_id, d.qcflag]));

flagColors = {

const uniqueFlagsInData = Array.from(new Set(qc_flags_data.map(d => d.qcflag))).sort((a, b) => a - b);

const uniqueFlagsWithZero = Array.from(new Set([0, ...uniqueFlagsInData])).sort((a,b)=> a-b);

const colors = d3.schemeTableau10;

const map = {};

let colorIndex = 0;

uniqueFlagsWithZero.forEach(flagValue => {

if (flagValue === 0) { map[flagValue] = "black"; }

else { map[flagValue] = colors[colorIndex++ % colors.length]; }

});

return map;

}

qcColorScale = (flagValue) => flagColors[flagValue ?? 0];

```

::: {.columns}

::: {.column width="70%"}

<!-- QC legend -->

```{ojs}

//| echo: false

//| eval: true

//| output: true

qcFlagLegend = {

try {

const uniqueFlagsWithZero = Object.keys(flagColors).map(Number).sort((a,b)=> a-b);

const tableRows = uniqueFlagsWithZero.map(flagValue => {

const flagColor = flagColors[flagValue]; // Use static map

const circles = flagNames.map(name => {

const mask = qcMasks[name];

const isSet = (flagValue & mask) > 0;

const circleFill = isSet ? flagColor : "#e0e0e0";

const circleSvg = `<svg width="15" height="15"><circle cx="7.5" cy="7.5" r="6" fill="${circleFill}" stroke="${isSet ? 'black' : '#ccc'}" stroke-width="1"></circle></svg>`;

return `<td style="text-align: center;">${circleSvg}</td>`;

}).join('');

const rowHeader = `<th scope="row" style="text-align: right; padding-right: 10px; white-space: nowrap;">

<span style="display: inline-block; width: 12px; height: 12px; background-color: ${flagColor}; border: 1px solid #555; margin-right: 5px; vertical-align: middle;"></span>

${flagValue === 0 ? 'Passed' : flagValue}

</th>`;

return `<tr>${rowHeader}${circles}</tr>`;

}).join('');

const headerCells = flagNames.map(name =>

`<th style="height: 100px; text-align: center; vertical-align: bottom; padding-bottom: 5px; font-size: 0.8em; white-space: nowrap;">

<span style="writing-mode: vertical-lr; transform: rotate(180deg);">${name.replace(/_/g, ' ')}</span>

</th>`

).join('');

const tableHeader = `<thead><tr><th style="vertical-align: bottom;">Flag Value</th>${headerCells}</tr></thead>`;

return html`<table style="border-collapse: collapse; margin-top: 10px; font-size: 0.9em; table-layout: fixed;">

${tableHeader}<tbody>${tableRows}</tbody>

</table>`;

} catch (error) {

console.error("Error generating QC Legend:", error);

return html`<div>Error generating QC Legend</div>`;

}

}

```

:::

::: {.column width="3%"}

<!-- empty column to create gap -->

:::

::: {.column width="27%"}

```{ojs}

//| echo: false

//| eval: true

//| output: true

leidenScaleAndLegend = {

let scale, legend;

try { // Add try...catch

// Check if query_data is ready and has 'leiden'

if (!query_data || query_data.length === 0 || !query_data[0].hasOwnProperty('leiden')) {

console.warn("Leiden data (query_data) not ready for legend/scale.");

scale = d3.scaleOrdinal().domain(["0"]).range(["grey"]); // Placeholder scale

legend = html`<div><ul style="list-style: none; padding-left: 0; margin-top: 10px; font-size: 0.9em;">

<li style="margin-bottom: 2px;"><span style="display: inline-block; width: 12px; height: 12px; background-color: grey; border: 1px solid #555; margin-right: 5px; vertical-align: middle;"></span> Cluster 0</li>

</ul>(Loading...)</div>`; // placeholder

} else {

const uniqueClusters = Array.from(new Set(query_data.map(d => d.leiden))).sort((a, b) => a - b);

scale = d3.scaleOrdinal(d3.schemeTableau10).domain(uniqueClusters);

const legendItems = uniqueClusters.map(cluster => {

const color = scale(cluster);

const clusterLabel = String(cluster);

return `<li style="margin-bottom: 2px;"><span style="display: inline-block; width: 12px; height: 12px; background-color: ${color}; border: 1px solid #555; margin-right: 5px; vertical-align: middle;"></span> Cluster ${clusterLabel}</li>`;

}).join('');

legend = html`<ul style="list-style: none; padding-left: 0; margin-top: 10px; font-size: 0.9em;">${legendItems}</ul>`;

}

} catch(error) {

console.error("Error generating Leiden Legend:", error);

scale = () => 'grey';

legend = html`<div>Error generating Leiden Legend</div>`;

}

return { scale, legend };

}

leidenColorScale = leidenScaleAndLegend.scale

leidenLegendHtml = leidenScaleAndLegend.legend

```

:::

:::

:::

::: {.column width="5%"}

:::

::: {.column width="55%"}

```{ojs}

//| echo: false

//| eval: true

//| message: false

//| output: false

d3 = require("d3@7")

width = 500

height = 500

marginTop = 20

marginRight = 20

marginBottom = 30

marginLeft = 40

xScale = d3.scaleLinear().domain([0, 1]).range([marginLeft, width - marginRight])

yScale = d3.scaleLinear().domain([0, 1]).range([height - marginBottom, marginTop])

svg = d3.create("svg")

.attr("width", width)

.attr("height", height)

.attr("viewBox", [0, 0, width, height])

.attr("style", "max-width: 100%; height: auto;");

xAxis = d3.axisBottom(xScale)

.ticks(width / 80)

.tickSizeOuter(0)

.tickSizeInner(-(height - marginTop - marginBottom));

yAxis = d3.axisLeft(yScale)

.ticks(height / 40)

.tickSizeOuter(0)

.tickSizeInner(-(width - marginLeft - marginRight));

gx = svg.append("g")

.attr("class", "x-axis")

.attr("transform", `translate(0,${height - marginBottom})`)

.call(xAxis);

gy = svg.append("g")

.attr("class", "y-axis")

.attr("transform", `translate(${marginLeft},0)`)

.call(yAxis);

svg.selectAll(".tick line")

.attr("stroke-opacity", 0.1);

svg.append("text")

.attr("x", width - marginRight)

.attr("y", height - marginBottom - 4)

.attr("fill", "currentColor")

.attr("text-anchor", "end")

.text("UMAP 1 →");

svg.append("text")

.attr("x", marginLeft + 4)

.attr("y", marginTop)

.attr("fill", "currentColor")

.attr("text-anchor", "start")

.attr("dominant-baseline", "hanging")

.text("↑ UMAP 2");

-

svg.append("clipPath")

.attr("id", "clip")

.append("rect")

.attr("x", marginLeft)

.attr("y", marginTop)

.attr("width", width - marginLeft - marginRight)

.attr("height", height - marginTop - marginBottom);

pointGroup = svg.append("g")

.attr("fill", "black")

.attr("clip-path", "url(#clip)");

```

```{ojs}

//| echo: false

//| eval: true

//| message: false

{ // Reactive block

const updateVisualization = () => {

const duration = 750;

const currentScale = colorby === "QC" ? qcColorScale : leidenColorScale;

if (!currentScale) {

console.error("Scale missing");

return;

}

if (!query_data || query_data.length === 0) {

console.warn("No data available for plotting.");

pointGroup.selectAll("circle").transition().duration(duration).attr("opacity", 0).remove();

return;

}

const xExtent = d3.extent(query_data, d => d.umap_1);

const yExtent = d3.extent(query_data, d => d.umap_2);

const xPad = (xExtent[1] - xExtent[0]) * 0.05;

const yPad = (yExtent[1] - yExtent[0]) * 0.05;

xScale.domain([xExtent[0] - xPad || -1, xExtent[1] + xPad || 1]);

yScale.domain([yExtent[0] - yPad || -1, yExtent[1] + yPad || 1]);

svg.select(".x-axis")

.transition().duration(duration)

.call(xAxis)

.on("start", () => {

svg.selectAll(".x-axis .tick line").attr("stroke-opacity", 0.1);

});

svg.select(".y-axis")

.transition().duration(duration)

.call(yAxis)

.on("start", () => {

svg.selectAll(".y-axis .tick line").attr("stroke-opacity", 0.1);

});

pointGroup.selectAll("circle")

.data(query_data, d => d.cell_id)

.join(

enter => enter.append("circle")

.attr("cx", d => xScale(d.umap_1))

.attr("cy", d => yScale(d.umap_2))

.attr("r", 2.5)

.attr("fill", d => {

try {

const valueToColor = colorby === "QC" ? qcFlagMap.get(d.cell_id) : d.leiden;

return currentScale(valueToColor) || 'grey';

} catch(e) { return 'grey'; }

})

.attr("opacity", 0)

.call(enter => enter.transition().duration(duration).attr("opacity", 0.8)),

update => update

.call(update => update.transition().duration(duration)

.attr("cx", d => xScale(d.umap_1))

.attr("cy", d => yScale(d.umap_2))

.attr("fill", d => {

try {

const valueToColor = colorby === "QC" ? qcFlagMap.get(d.cell_id) : d.leiden;

return currentScale(valueToColor) || 'grey';

} catch(e) { return 'grey'; }

})

.attr("opacity", 0.8)

),

exit => exit

.call(exit => exit.transition().duration(duration).attr("opacity", 0).remove())

);

};

try {

updateVisualization();

} catch(error) {

console.error("Error during D3 updateVisualization:", error);

}

return svg.node();

}

```

In the dot plot on the bottom left provides a QC flag legend. For example, QC flag '5' represents cells that were flagged for having low counts and low features whereas QC flag '96' represents cells that wee flagged for FOV QC as wells as low SBR.

:::

::::

If you want to further explore this subset, you can examine the `query_data`

and `qc_flags_data` dataframes below.

```{webr}

#| autorun: true

#| input:

#| - query_data

#| - qc_flags_data

head(query_data)

head(qc_flags_data)

```

:::

:::

For the remainder of this chapter, I will focus on the PR-based

method.

I find it's helpful to:

1. Have more control of the plotting aesthetics and label multiple sub-clusters

of a given Leiden cluster for clarity and

2. isolate the Leiden clusters and visualize them in both

UMAP space and physical (XY) space to see if there are regions in the tissue that

might provide clues about the cell types.

Instead of the default `plotDots` colors, let's define our own.

```{r}

#| label: V-1

#| eval: false

#| code-summary: "R Code"

#| code-fold: true

# define colors semi-manually instead of using the default colors

column <- 'leiden_pr'

column_levels <- levels(py$adata$obs[[column]])

n_levels <- length(column_levels)

if(n_levels<27){

colors_use <- pals::alphabet(n_levels)

} else if(n < 53){

colors_use <- c(pals::alphabet(26), pals::alphabet2(n_levels-26))

} else {

stop("consider fewer groups")

}

names(colors_use) <- column_levels

# saving colors for later

results_list[['leiden_global_names']] <- names(colors_use)

results_list[['leiden_global_colors']] <- as.character(colors_use)

saveRDS(results_list, results_list_file)

```

Plot the cells in XY space and UMAP space and color based on `leiden_pr`.

```{r}

#| label: V-2

#| eval: false

#| code-summary: "R Code"

#| code-fold: true

group_prefix <- "leiden" # <1>

pp_assets_dir <- file.path(analysis_asset_dir, "preprocessing")

# XY (global only)

plotDots(py$adata, color_by='leiden_pr',

plot_global = TRUE,

facet_by_group = FALSE,

additional_plot_parameters = list(

geom_point_params = list(

size=0.001

),

scale_bar_params = list(

location = c(5, 0),

width = 2,

n = 3,

height = 0.1,

scale_colors = c("black", "grey30"),

label_nudge_y = -0.3

),

directory = pp_assets_dir,

fileType = "png",

dpi = 200,

width = 8,

height = 8,

prefix=group_prefix

),

additional_ggplot_layers = list(

theme_bw(),

xlab("X (mm)"),

ylab("Y (mm)"),

coord_fixed(),

scale_color_manual(values = colors_use),

theme(legend.position = c(0.8, 0.4)),

guides(color = guide_legend(

title="Leiden (PR)",

override.aes = list(size = 3) ) )

)

)

# XY (facets only)

plotDots(py$adata, color_by='leiden_pr',

plot_global = FALSE,

facet_by_group = TRUE,

additional_plot_parameters = list(

geom_point_params = list(

size=0.001

),

scale_bar_params = list(

location = c(5, 0),

width = 2,

n = 3,

height = 0.1,

scale_colors = c("black", "grey30"),

label_nudge_y = -0.3

),

directory = pp_assets_dir,

fileType = "png",

dpi = 100,

width = 5,

height = 5,

prefix=group_prefix

),

additional_ggplot_layers = list(

theme_bw(),

xlab("X (mm)"),

ylab("Y (mm)"),

coord_fixed(),

scale_color_manual(values = colors_use),

theme(legend.position = c(0.8, 0.4)),

guides(color = guide_legend(

title="Leiden (PR)",

override.aes = list(size = 3) ) )

)

)

# UMAP (global only)

plotDots(py$adata,

obsm_key = "umap_pr",

color_by='leiden_pr',

plot_global = TRUE,

facet_by_group = FALSE,

additional_plot_parameters = list(

geom_point_params = list(

size=0.001, alpha=0.1

),

geom_label_params = list(

size = 4

),

labels_on_plot = data.frame(),

directory = pp_assets_dir,

fileType = "png",

dpi = 200,

width = 8,

height = 8,

prefix=group_prefix

),

additional_ggplot_layers = list(

theme_bw(),

xlab("UMAP 1"),

ylab("UMAP 2"),

coord_fixed(),

scale_color_manual(values = colors_use),

# guides(color = guide_legend(

# title="Cell Type",

# override.aes = list(size = 3) ) ),

theme(legend.position = "none")

)

)

# UMAP (facets only)

plotDots(py$adata,

obsm_key = "umap_pr",

color_by='leiden_pr',

plot_global = FALSE,

facet_by_group = TRUE,

additional_plot_parameters = list(

geom_point_params = list(

size=0.001, alpha=0.1

),

geom_label_params = list(

size = 2

),

labels_on_plot = data.frame(),

directory = pp_assets_dir,

fileType = "png",

dpi = 100,

width = 5,

height = 5,

prefix=group_prefix

),

additional_ggplot_layers = list(

theme_bw(),

xlab("UMAP 1"),

ylab("UMAP 2"),

coord_fixed(),

scale_color_manual(values = colors_use),

guides(color = guide_legend(

title="Cell Type",

override.aes = list(size = 3) ) )

)

)

```

1. in the plotting below, we will use this name to parse out files.

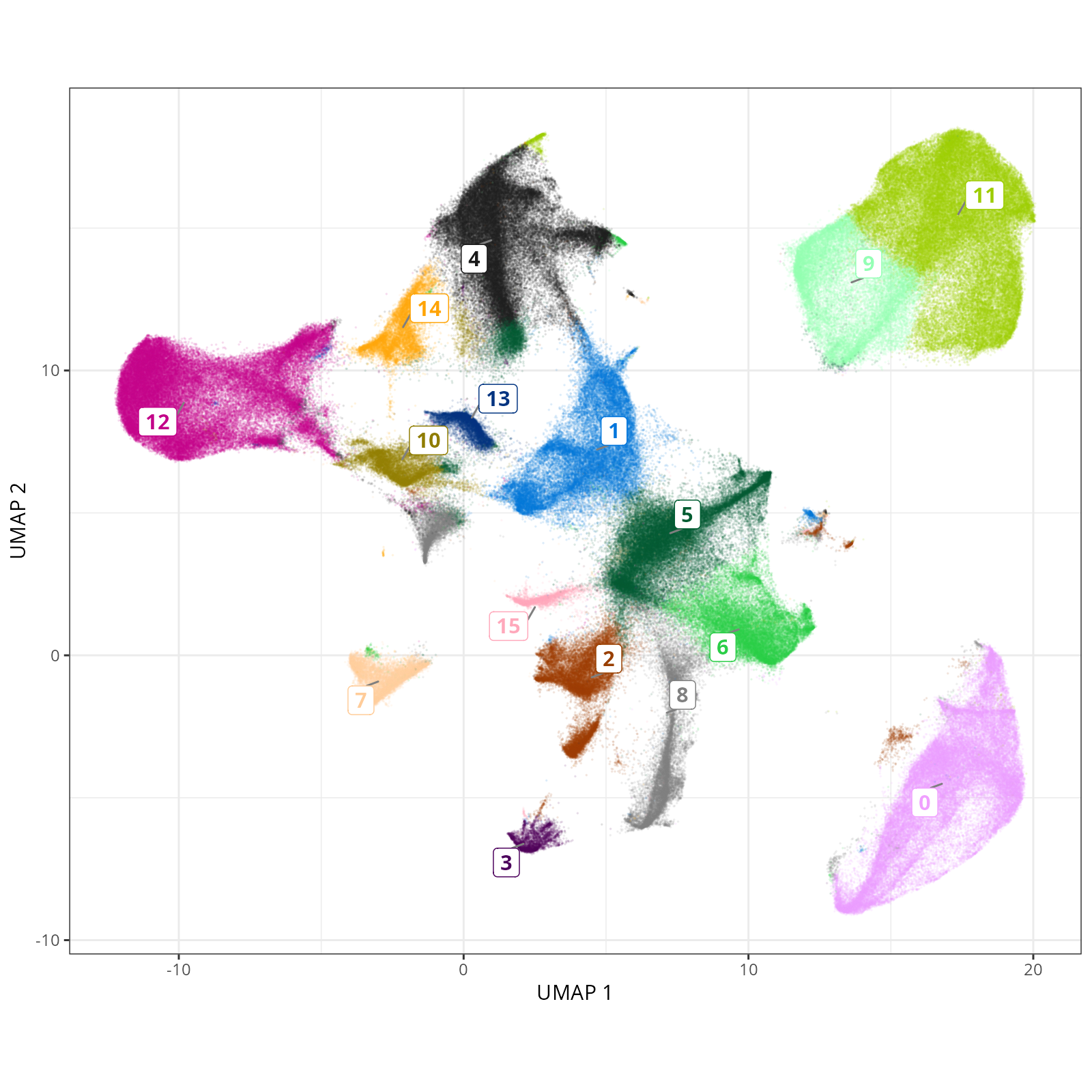

Here are the overall (global) plots.

::: {.panel-tabset}

#### Leiden - UMAP

```{r}

#| label: fig-umap-leiden

#| message: false

#| warning: false

#| echo: false

#| fig.width: 6

#| fig.height: 5

#| fig-cap: "UMAP with Leiden (PR-based) cells."

#| eval: true

knitr::include_graphics(file.path(analysis_asset_dir, "preprocessing", "leiden__umap_pr__S0__plot.png"))

```

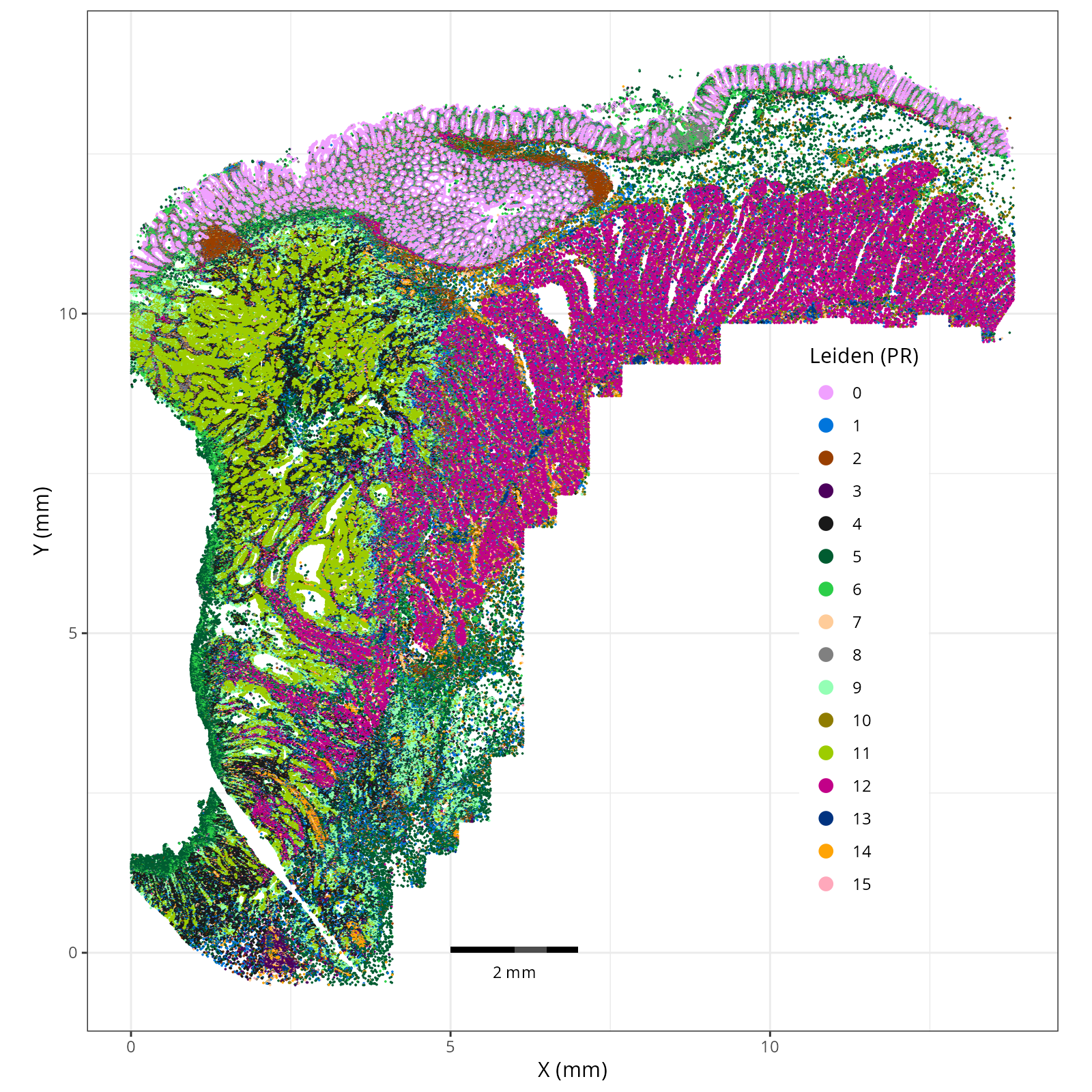

#### Leiden - XY

```{r}

#| label: fig-xy-celltype-broad

#| message: false

#| warning: false

#| echo: false

#| fig.width: 6

#| fig.height: 5

#| fig-cap: "XY with Leiden (PR-based) cells."

#| eval: true

knitr::include_graphics(file.path(analysis_asset_dir, "preprocessing", "leiden__spatial__S0__plot.png"))

```

:::

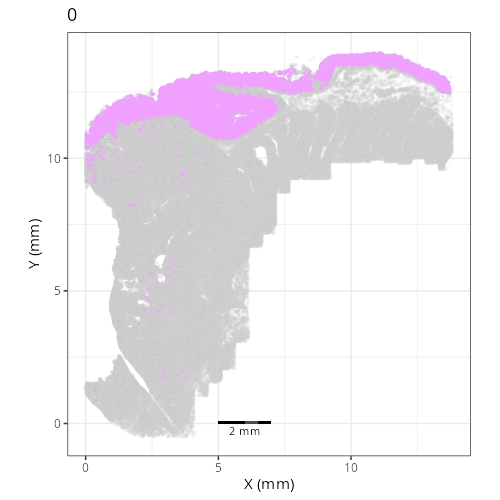

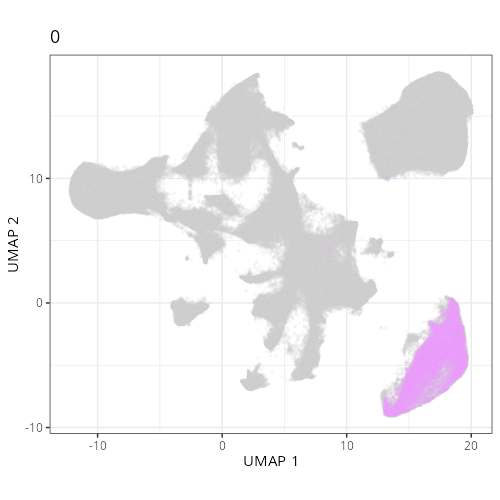

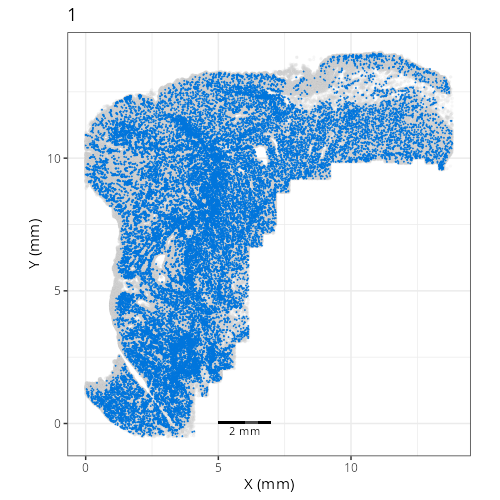

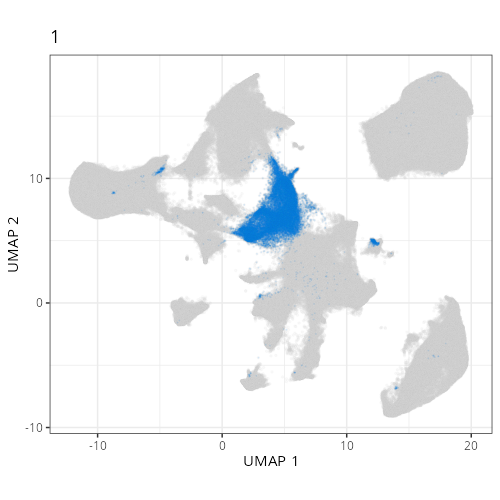

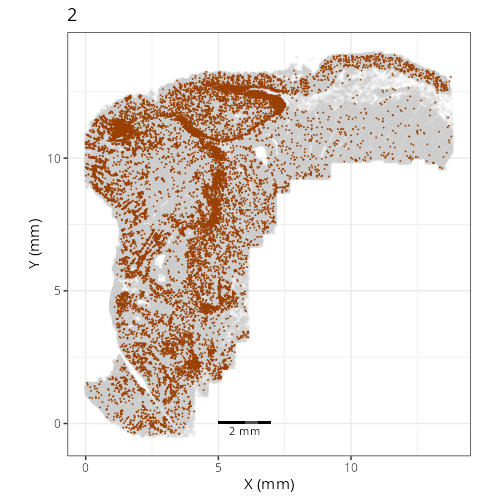

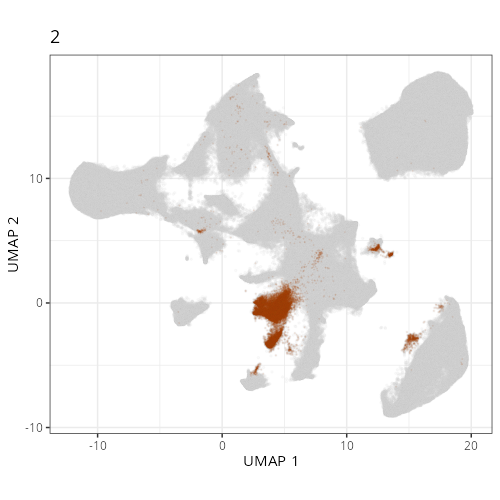

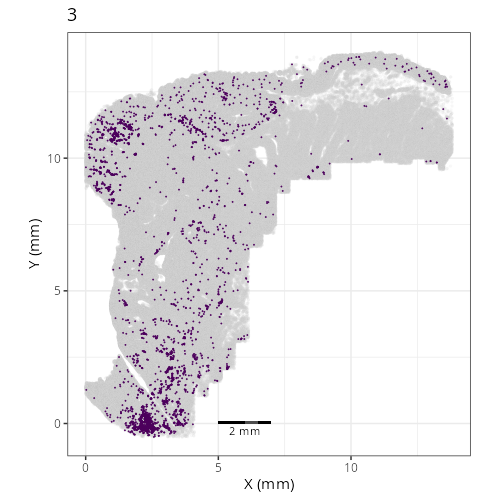

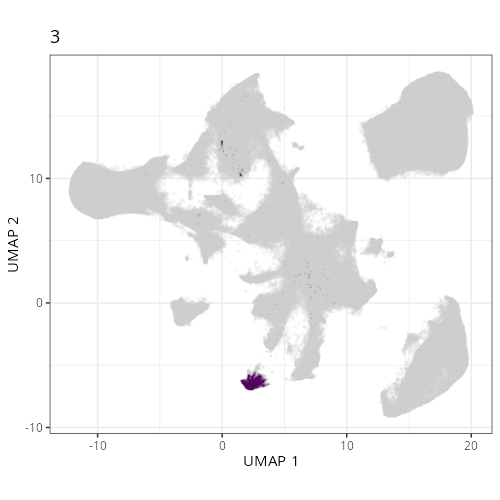

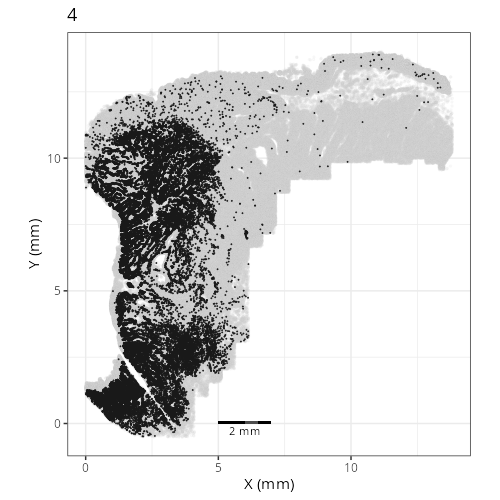

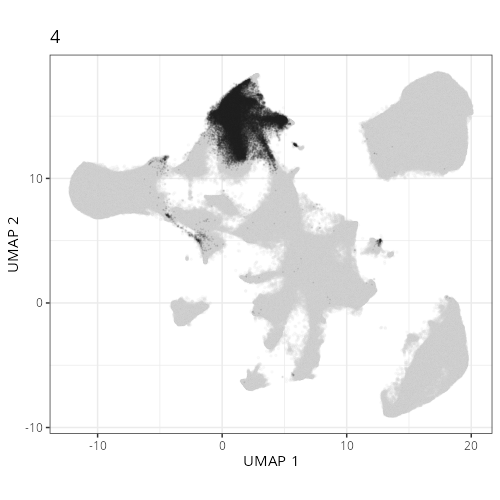

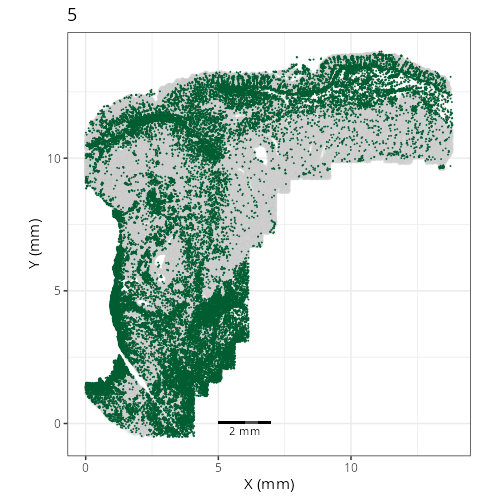

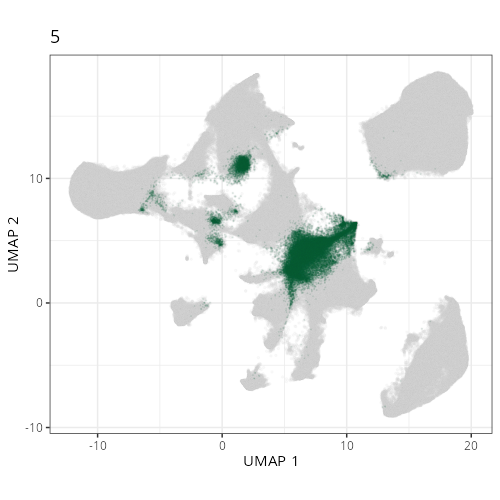

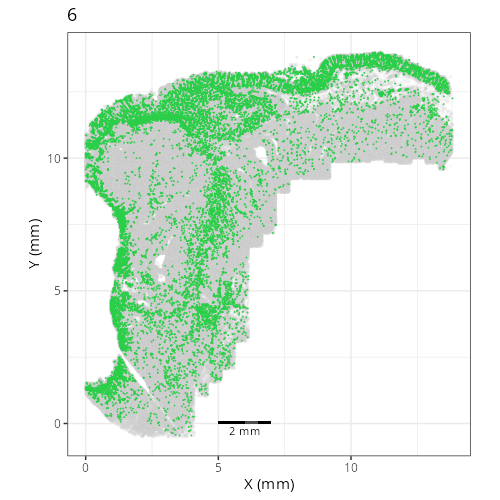

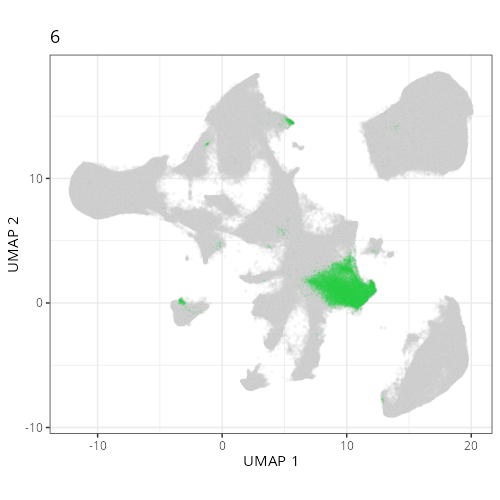

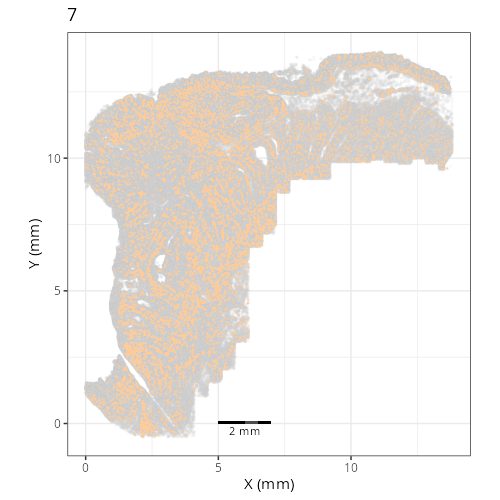

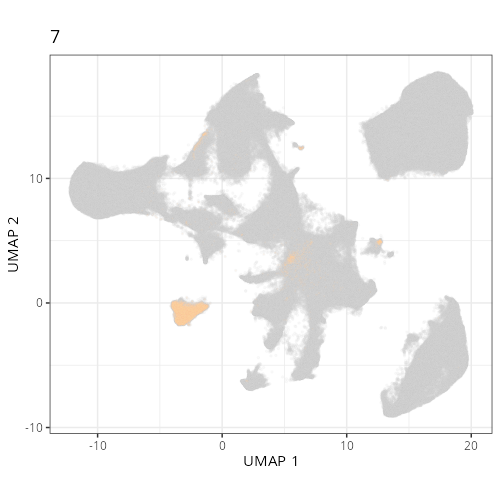

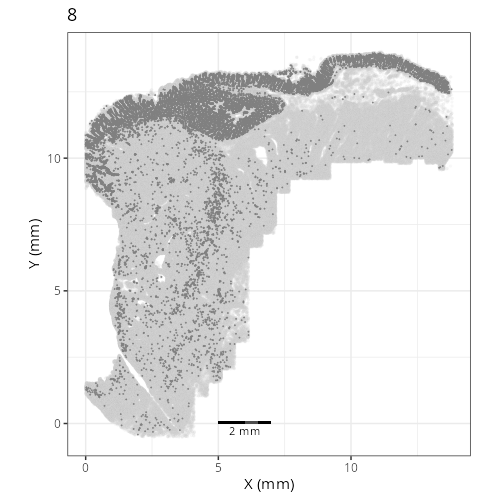

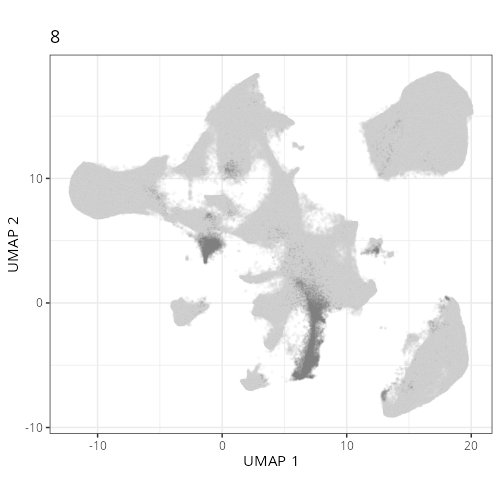

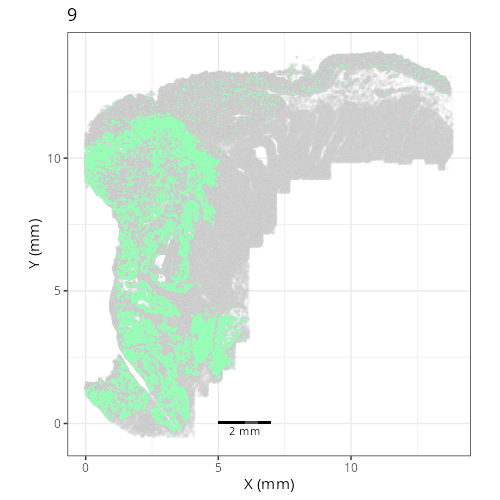

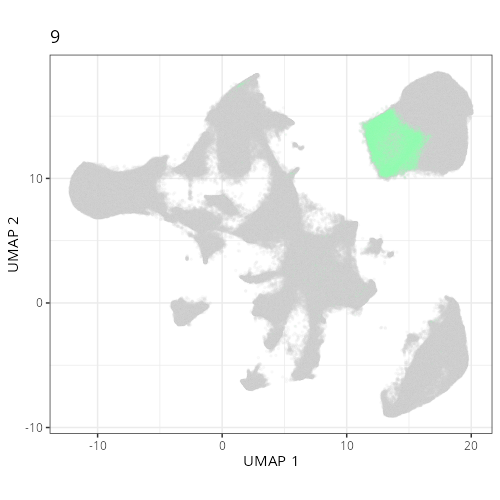

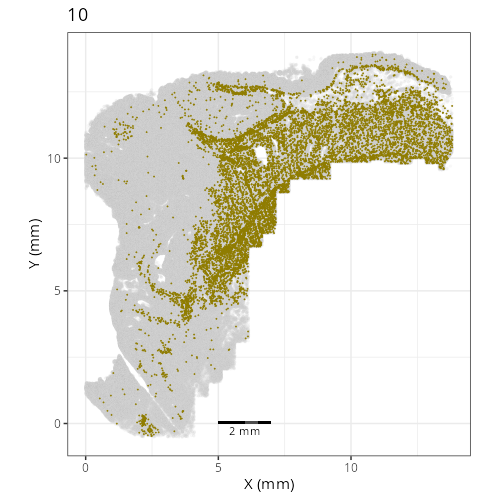

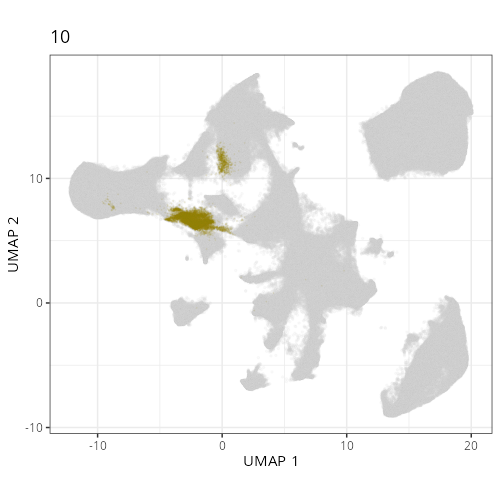

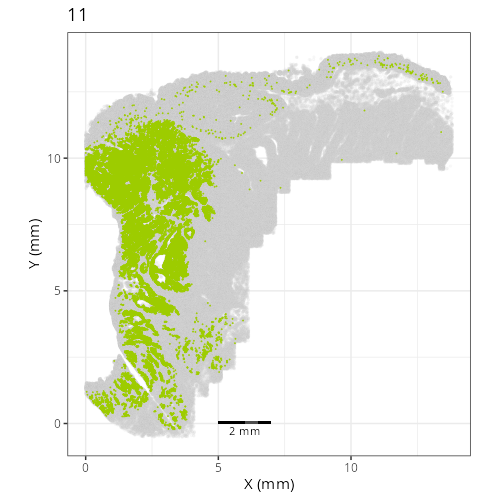

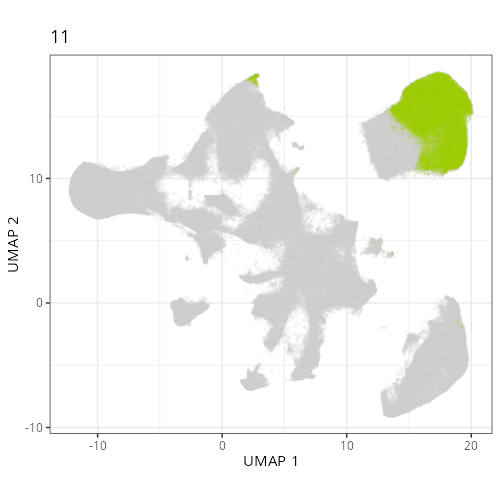

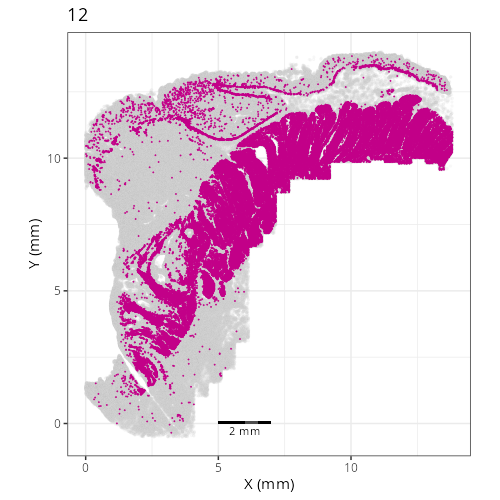

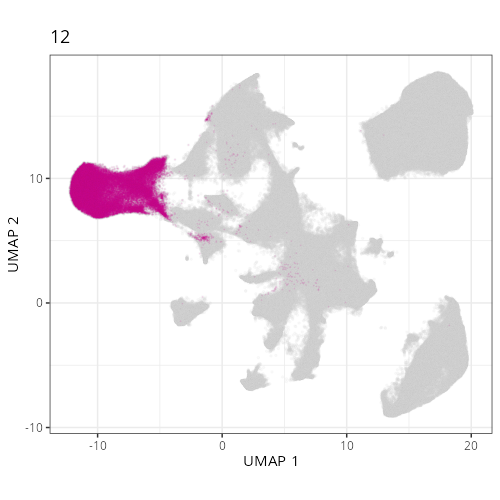

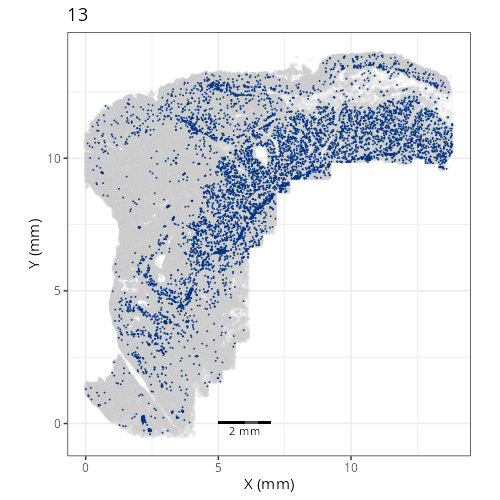

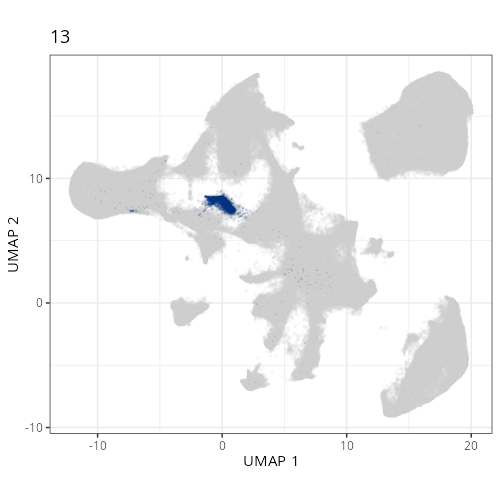

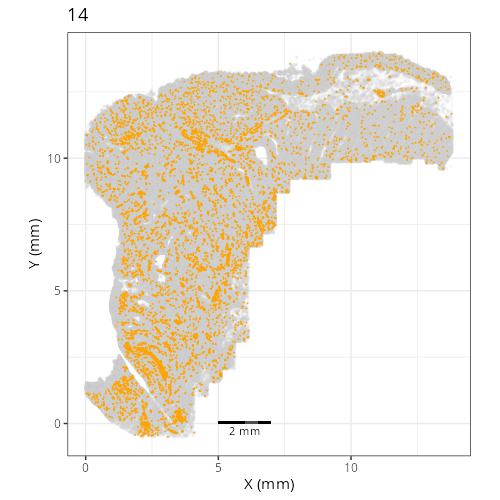

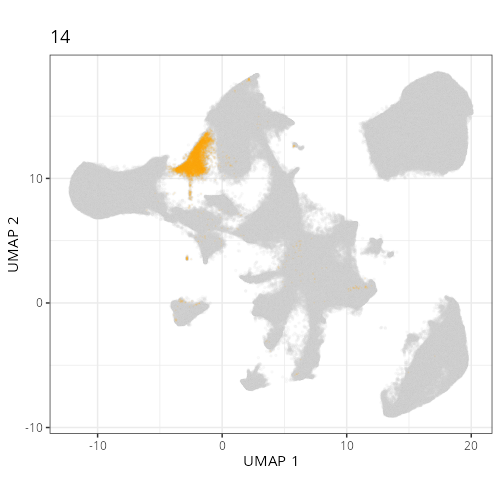

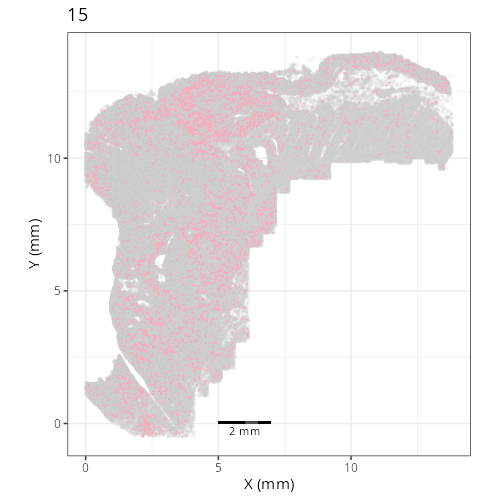

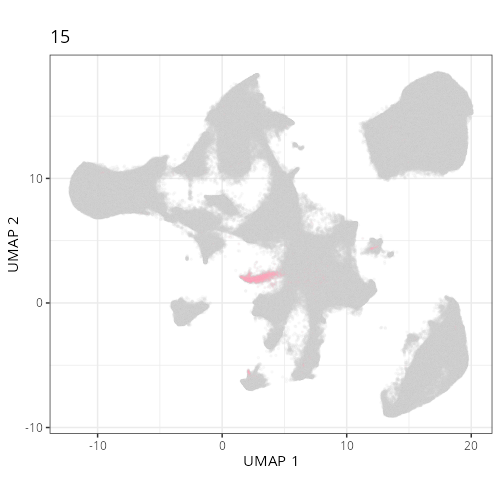

Here are the individual plots[^2] we created organized by Leiden cluster. From these

pairs of plots one can quickly see how some Leiden clusters are spatially restricted.

For example, Leiden 0 consists of cells in the top part of the tissue (_i.e._,

the non-tumoral epithelium). Similarly, cluster 12 occupies the left-most region

of the tissue.

::: {.panel-tabset}

```{r}

#| output: asis

#| eval: true

#| code-fold: true

#| echo: false

fig_dir <- file.path(analysis_asset_dir, "preprocessing")

group_prefix <- "leiden"

slide_id <- "S0"

xy_files <- Sys.glob(file.path(fig_dir,

paste0(group_prefix,

"__spatial__", slide_id, "__facet_*png")))

org_order <- as.numeric(gsub(".png", "", unlist(lapply(strsplit(xy_files, split="_facet_"), "[[", 2L))))

xy_files <- xy_files[match(sort(org_order), org_order)]

umap_files <- Sys.glob(file.path(fig_dir,

paste0(group_prefix,

"__umap_pr__", slide_id, "__facet_*png")))

org_order <- as.numeric(gsub(".png", "", unlist(lapply(strsplit(umap_files, split="_facet_"), "[[", 2L))))

umap_files <- umap_files[match(sort(org_order), org_order)]

res <- purrr::map2_chr(xy_files, umap_files, \(current_xy_file, current_umap_file){

knitr::knit_child(text = c(

"### `r gsub('.png', '', strsplit(current_umap_file, split='__facet_')[[1]][2])`",

"",

":::{columns}",

"",

"::: {.column width='40%'}",

"",

"```{r eval=TRUE}",

"#| echo: false",

"knitr::include_graphics(current_xy_file)",

"```",

"",

":::",

"",

"::: {.column width='10%'}",

"",

":::",

"",

"::: {.column width='40%'}",

"",

"```{r eval=TRUE}",

"#| echo: false",

"knitr::include_graphics(current_umap_file)",

"```",

":::",

"",

":::",

"",

"",

""

), envir = environment(), quiet = TRUE)

})

cat(res, sep = '\n')

```

:::

## Conclusion

And with that, we've navigated the essential pre-processing steps. Starting with

our quality-controlled cell data, we applied normalization to account for

technical variations, identified the most informative genes, and used PCA to

reduce the data's dimensionality. Building upon this foundation, we generated

UMAP embeddings for visualization and performed Leiden clustering to partition

the cells into distinct groups based on their expression profiles.

The interactive exploration highlighted a critical point: parameters matter.

Choices made during normalization, dimensionality reduction, and clustering

significantly influence the final UMAP layout and cluster assignments. There

isn't a single "correct" set of parameters, but understanding their effects

allows you to tailor the analysis to best reveal the biological structures

relevant to your specific questions.

The resulting AnnData object, now enriched with normalized data layers, PCA

coordinates, UMAP embeddings, and Leiden cluster labels, is primed for the next

crucial phase: assigning biological meaning to these patterns. In the following

chapters we will delve into grouping cells based on their spatial domain and their

cell types.

[^1]: when I tried using the `sc.experimental.pp.normalize_pearson_residuals` method

on this dataset, the OS crashed (>200 GBs of RAM).

[^2]: To see how to generate this type of output,

click the `</>` icon on the top right of this chapter and then click `view source`.